Tuesday, June 26, 2012

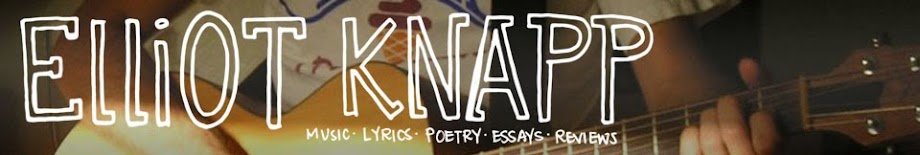

Kate Bush - The Dreaming

The Dreaming--Kate Bush's fourth album, arriving less than five years after her debut--has got me thinking about a whole mess of different things. Approaching her music fairly indirectly (not having been around when the music was new [no real change there!], or being a hardcore fan, and not having much of an interest in 80's pop music) made for slow progress in appreciating it, but a couple of years have provided an enlightening and broadening experience in getting to know and learn from this music.

While I agree with most fans that Hounds of Love is her most distinctive and cohesive set, this album makes a close second for many of the same reasons. Partially fulfilling her move toward tighter pop structures and chic sounds of the day, the songs here continue to move away from the more traditional (especially piano-dominated) instrumentation of her first albums into an area where 80's synths and effects surround the songs' core piano parts and multi-part structures juxtapose wildly different styles within pop-length tracks, with Bush's multi-tracked vocals calling and responding in an often bizarre array of different vocal deliveries. Needless to say, these songs can come across as difficult to penetrate at first, a fact that's not helped by the fact that the late-80's CD reissue is in dire need of remastering, making the already-difficult songscapes even tougher to perceive because of the mediocre sound reproduction.

Nevertheless, this shit's awesome! What's especially interested me lately is the fine balance Bush strikes between weirdness, progressive and experimental complexity, and pop accessibility. When I say "weirdness" I mean things like singing in a weird voice (like those shrill backing vocals that nobody else has really done the same way), laying a really strange-sounding effect on a guitar line, or singing Australian narratives and utilizing native Australian instruments. Weirdness is a great attention-getter, and is a great way to make music distinctive and set it apart from the vast pack of musicians out there just trying to make something that sounds pretty and inoffensive in hopes that it'll appeal to the largest audience possible. However, weirdness alone isn't enough to keep my attention long-term. Really, the lukewarm feelings I get from a lot of today's music come from a feeling that weirdness and style often outweigh the actual content of the songs, music, lyrics etc. Not that every artist should be changing time signatures every two measures and shredding ridiculously difficult guitar parts for music to be considered good, but there's more to making some distinctive music than singing a tired indie breakup song in an overwrought plaintive voice over eighth-note staccato power chords.

What I love about Kate Bush is how well she backs up her weirdness with musical substance--every song has a discreet feel, be it narrative or more philosophical, and upon close examination it seems that every element of the song is carefully tailored to fulfill the song's conceptual promise, from playfully poetic lyrics to song sections that brilliantly channel Bush's twisting moods with shifting timbres and pacing (see "Pull Out the Pin," "Night of the Swallow") to vastly differing stylistic experiments between pounding, expansive rock like "Sat In Your Lap" and waltzing existential pop like "Suspended in Gaffa."

Finally, I'm continually amazed by how poppy the music ultimately is--in spite of the fact that she's often reimagining and further developing a lot of concepts explored by then-and-now-villified progressive musicians when the genre was all but completely forced from mainstream interest, Bush manages to maintain a pure, sincere emotional core along with a buoyant conciseness that makes these songs accessible in spite of their complexity. Even more, she's still making new fans 30 years later in spite of the extreme 80's vibe, although that's a retro aesthetic that's still currently regarded as "ok" with today's young music fans. I'm sure it doesn't hurt that her visual aesthetic pretty much rivaled her musical one--if only today's pop songstresses could back up their audacious imagery with such equally challenging music! Anyway, good on KB for proving that great pop doesn't have to skimp on nuance, and for helping me expand into some new musical areas. This makes me want to check out some of her more recent work...

Get it here.

Friday, June 22, 2012

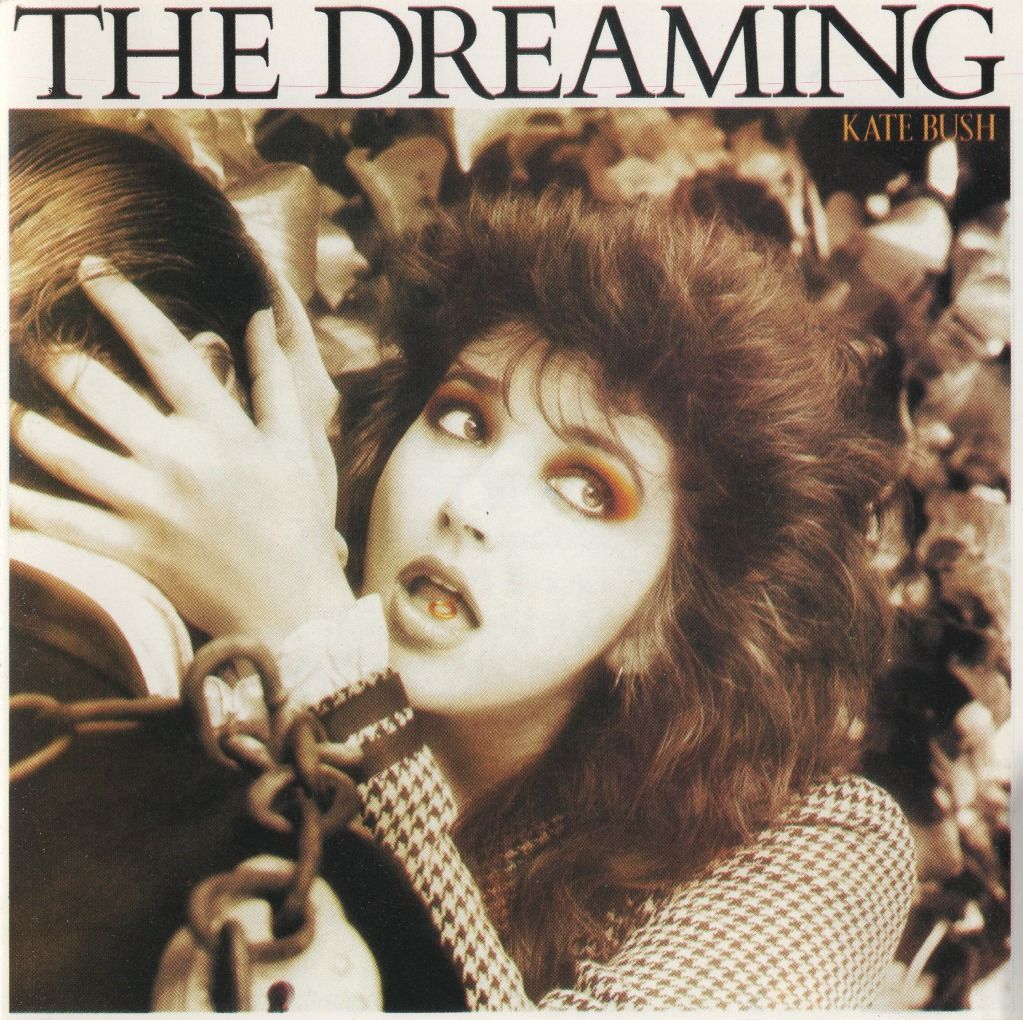

Tomasz Stańko - Music for K

These days, what's probably the biggest obstacle for Polish trumpeter Tomasz Stańko's 1970 debut is that it says "Polish Jazz" in the top left corner, leading to some reasonable assumptions that it's going to be some sort of fusion of polka or mazurka and American jazz, and some perhaps less justified assumptions that it'll be crap jazz because it's not American. Not only are both of these assumptions proven incorrect by the music contained in these (digital) grooves, an album like this provides key evidence of the roots of the compositional framework that British/European jazz fusion bands like Nucleus and The Soft Machine utilized in the mid-1970's, but also that the narrative of jazz history in Europe is unjustifiably incomplete and marginalized in comparison with that of America.

Now, anybody in the know about this period of European jazz will probably acknowledge that I'm sort of getting ahead of myself by starting with Stańko's debut--many would cite Krzysztof Komeda's 1966 album Astigmatic as the most important illustration of the above points...in my own feeble defense, let's just say that this was the album I decided to review today for no other reason than that it's the one my eyes landed upon and seemed like a good one to write about. Music for K is indeed a tribute to the late Komeda, on whose watershed Astigmatic album Stańko also played trumpet, and who is credited with contributing heavily to the development of a distinct flavor of European jazz that started in the 1960's and has continued to present. Assigning credit is important but not as much as acknowledging a quality piece of work. Here the influence of Komeda (who also had extensive film score experience including Roman Polanski's Rosemary's Baby) and Astigmatic are felt both in a sense of cinematic drama and a tonal palette that trades much of American jazz's jubilant euphoria for a darker, more cerebral form of expression.

The opener "Czatownik" both recalls Komeda's descending chromatic piano themes and predicts the tangled melodies that the aforementioned electric fusion groups would favor, with alto and tenor saxophones blurting rapid fire unison themes with the trumpet before things start to get more shambling, with each voice separating into an upward call that again lines up for a dramatic fanfare. One of the things I really appreciate about this music is the shifting dynamics--things can go from blaring horns to sizzling quiet in an instant--the bass and drum interaction is prime here (check out that drum sound around 3:30)--and the piano-less lineup both points to the absent Komeda and allows for alternation between skeletal frameworks and a spotlight on the wind instruments' melodies, not to mention a huge potential for free playing, of which there is an abundance.

In trying to define the specifics of a "European" jazz sensibility, my instincts are to point at its richly developed classical tradition, which seems to be borne out in a predilection for ostinato (check out the gently pulsing reeds in "Nieskonczenie Maly," and their darker, more anguished and dissonant counterparts in "Cry") and song structures that seem more linear than the typical circular jazz structures (head, solo:, head). Things reach their freest and most intense in the 16-minute title track, which climbs a series of crescendos and mini-dips to a collective caterwaul, then steps back down across one of the album's greatest drum showcases to a squawking conclusion.

More than anything, the quality and energy of the playing on this album raises questions about the relative obscurity of the players here and severely shakes my confidence in a completely American-centric jazz narrative...we need better informational resources and access to more great music like this! On the plus side, if you're feeling like you've exhausted the available avant-garde American jazz and everything's sounding a bit too happy and boppy for you, maybe there's hope in the Old World's "new" jazz--who knows what else we're still missing!

Get it here

Tuesday, June 5, 2012

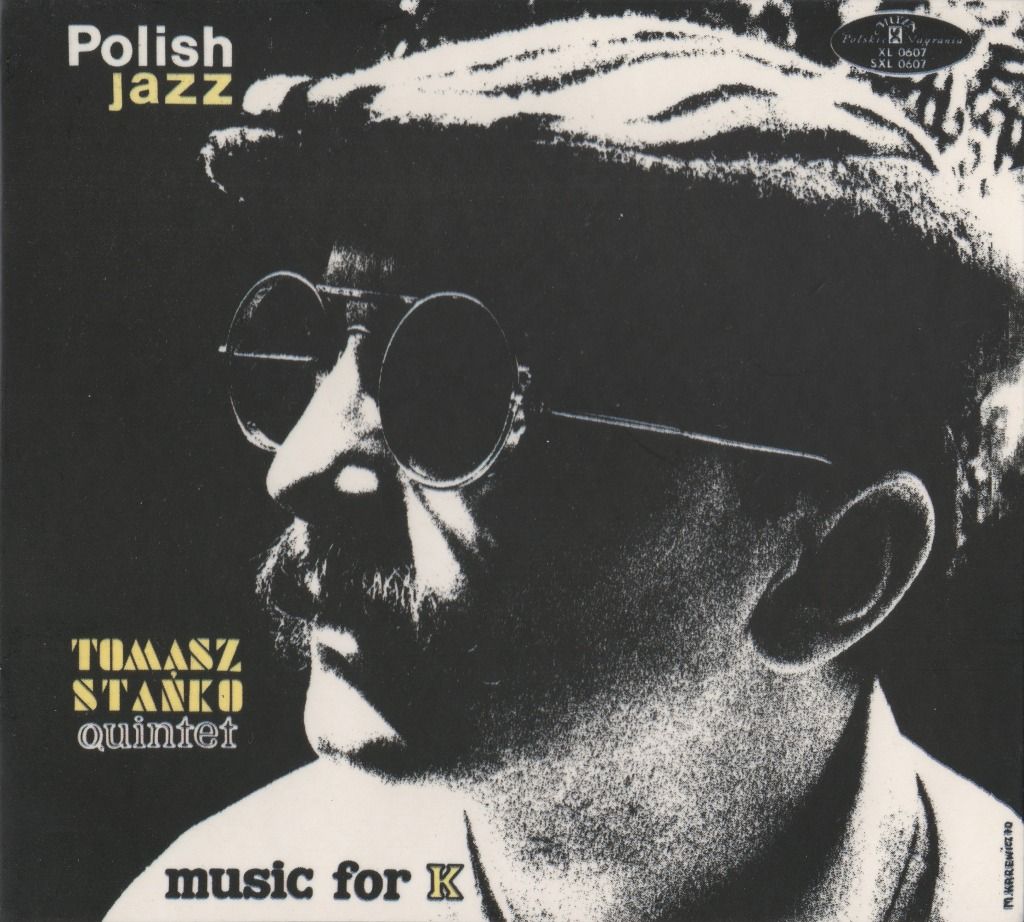

Davy Graham - Anthology: 1961-2007 Lost Tapes

Almost four years after Davy Graham's death, the folks at Les Cousins Music are still working not only to preserve his officially-recorded legacy, but also to expand the scope and depth of his output, making it clearer for those who weren't there why the guitarist was the undisputed king of the 1960's English folk revival. Nostalgically packaged in a collage of images gleaned from Graham's personal scrapbook (and simultaneously displaying both spellings of the guitarist's first name he confoundingly vacillated between), this three-CD collection anthologizes no less than 54 tracks across more than 2 1/2 hours of unreleased recordings. Count me in!

It's a fool's errand to attempt a track-by-track analysis of an anthology so deep, so I'll attempt to convey some general impressions and reference tracks where appropriate. Having been a Davy Graham fan for several years, I think I'm finally starting to understand how, as Roy Harper says, Graham "never managed to turn his talent into a brand that people could go out and buy and enjoy," yet every other guitarist from the same time period and beyond cites Graham as a towering giant of the six-string. After five years of absorbing Graham's studio output I'm still at a loss to recommend a single album of his that fully conveys and encompasses what was so revolutionary about his playing, and not having been there it's been hard to picture myself in that bright-eyed hopeful time and imagine myself at some bohemian party with Graham conjuring untold spirits out of an acoustic while everyone just sits and listens. Enter this anthology, which as far as I've heard does the best job this side of After Hours at Hull University

Since it's mostly just an acoustic with or without vocals, the sound quality isn't much of a bother--if anything, it enhances the intimacy of the performances, which find Graham energetically blasting solo performances of many of the folk and blues songs found on his albums as well as never-before-heard tracks. Throughout, his technique is astounding, transitioning as quickly as ever between lead and rhythm, melody and harmony, from style to style. Somehow the setting's informality allows the guitarist's hard-won chops to shine brighter with none of the studio adornments meant to commercialize his sound, and we instead get to hear him exclaim "Ah, fuck" after some imperceptible mistakes during a lightning-fast take on Leadbelly's "Fannin Street" with nary a missed note, as well as a verbal introduction to his classic instrumental "Anji" (there are two versions here, along with an unreleased track and album highlight "Anji's Greek Cousin") that details how he wrote the tune. While the live renditions of guitar-and-vocal folk/blues tunes present uniformly great guitar and often contain vocals that are superior to the studio versions, they also miss the mark when it comes to what made the guitarist unique--more than almost any other Graham album, this anthology conveys the strange alchemy that occurred between Graham's musical influences, his fingers and his guitar, and these discs present ample, undiluted evidence of what was possible when only these elements were on display.

Of the three discs, the third is probably the least essential, reflecting the diminishing returns that Graham's post-60's releases offer, yet it often sounds more vital than studio recordings from the same period. Though Graham's lifestyle choices and age would gradually slow his playing and attenuate his already limited vocals, we still get some surprisingly good representations of the more delicate British folk, jazz, medieval-sounding instrumentals and world folk music explorations he continued to make through the 70's and beyond. "The Gold Ring" shows his pull-off speed undiminished, "Sita Ram" and "Mevlut" pair his further eastern experiments with appropriate accompaniment, and "DeVisee Suite" shows a subtle, slower side to his playing that was all but absent in the early days. The final late-period tracks remind us that we're summing up the career accomplishments and contributions of a distinctive force in 20th century popular music. As with his 2007 swansong Broken Biscuits, the joy here comes less from marveling at jaw-dropping speed, but more from giving credit where it's due and appreciating that the man's muse was still active at the end.

While I still think it's impossible to recommend an accurate starting point for a prospective Davy Graham fan (it takes more than the average time investment to really "get" him as an artist), this anthology is a surprisingly worthy addition to even a modest Davy Graham collection. Unlike so many retrospective collections, it manages (with the help of Graham's considerable skill and restlessness) to make familiar songs sound fresh and new songs sound immediate and relevant to the further-broadening portrait available of Graham as an artist.

Get it here

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)