` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` `

Tuesday, August 30, 2011

"Come November" Video

Here's a video of one of my new-ish songs, the uncharacteristically politics-focused "Come November." Lyrics (there are a lot of them) and more info over at the song page, but I'll add that there's a brief melodic quote from a classic American folk song. Which one?

Sunday, August 28, 2011

The Incredible String Band - The 5000 Spirits or the Layers of the Onion

The Incredible String Band managed to make a pretty impressive change between the tame contemporary folk of their 1966 debut and this, their second long-player, which finds the core duo formulating their idiosyncratic classic sound around an increasingly strong set of songs. It's also the first album where Mike Heron and Robin Williamson begin to live up to the promise of their band's name, expanding their instrumental repertoire to include sitar, gimbri, oud, and tamboura, in addition to the more traditional guitar, fiddle and mandolin they'd already been using.

Of course, playing weird instruments alone a great album does not necessarily make. Without Heron and Williamson's songwriting, chemistry as performers, and the bizarre fusion of world music, more traditional blues and folk, progressive song structures and budding interest in world religions, The Incredible String Band might just sound like every other British 60's folk revival group. The more I revisit my favorite ISB albums, the more interesting I find the combination of Heron's and Williamson's songs. As far as I know, they never really collaborated in co-writing, yet there's a wide-eyed optimism and mystical euphoria that pervades both writers' contributions. With further listening, though, it becomes easier to identify Heron's (the deeper, rounder voice) songs for their whimsy and pop instincts, and Williamson's (the more nasally voice) for their focus on narration and more abstract, eerie imagery. Most people I've talked to about the ISB have a preference for one or the other (I probably like Williamson's more, though Heron's voice is easier on the ears), but the magic of the duo is how well their albums flow between the two writers' songs and how well they both contribute to one another's songs.

By most music fans' standards, The Incredible String Band is quite eccentric and usually elicits divisive reactions. Interestingly enough, the things that most haters complain about--the vocal style, the duo's amateur skills at some of their strange stringed instruments, their hippie ideals, and their proclivity for meandering, twee and overt mysticism--are the precise things that fans of the group love about them. While I totally understand many of these criticisms (many of these songs aren't really the kind of "pretty" music you'd probably expect from a 60's folk duo), I'm obviously in the latter camp. I'd even go so far as to say that there haven't been enough groups making music like this, and that it's heavily influenced my own choices as a musician. That is, acoustic music that is experimental, eclectic, heedless of fashion and conventions, and also transcends the typical trappings of folk, singer/songwriter and pop (other notable practitioners of this underdeveloped approach include Comus, Roy Harper, Tudor Lodge, and maybe Kevin Coyne and Robbie Basho). The Incredible String Band is gloriously unusual in a way that's both deliberate and completely natural, and I don't think they've been matched in their field.

While the band's next album, The Hangman's Beautiful Daughter, is probably their strongest and most imbued with vision and taste, this album has some of their finest (simply) songs. From infectiously catchy and whimsical Heron contributions like the hand-percussion workout "Little Cloud," the sweet metaphor and harmonies of "Painting Box," and Caribbean inflection and great slide guitar of "The Hedgehog's Song" to Williamson's tender highlight "First Girl I Loved" and twisted folk revival deconstruction "No Sleep Blues," the duo turns in some of the most accessible songcraft of their career. And then there's songs like the hazy "Chinese White" with its incantatory rhythm and fiddle, and Williamson's fantastically knobbly "The Mad Hatter's Song," which reveals its author as both a progressive visionary and an able poet. Though a few songs lean a little too heavily on established folk music tropes and a few others fail to be made of the memorable stuff of the album's highlights, The 5000 Spirits or the Layers of the Onion is a worthy cornerstone in the ISB's discography and one of the furthest-out albums of 1967. To say that this album and its successor profoundly influenced a lot of great British psychedelic and progressive music that was soon to come would be a flagrant understatement.

Wednesday, August 24, 2011

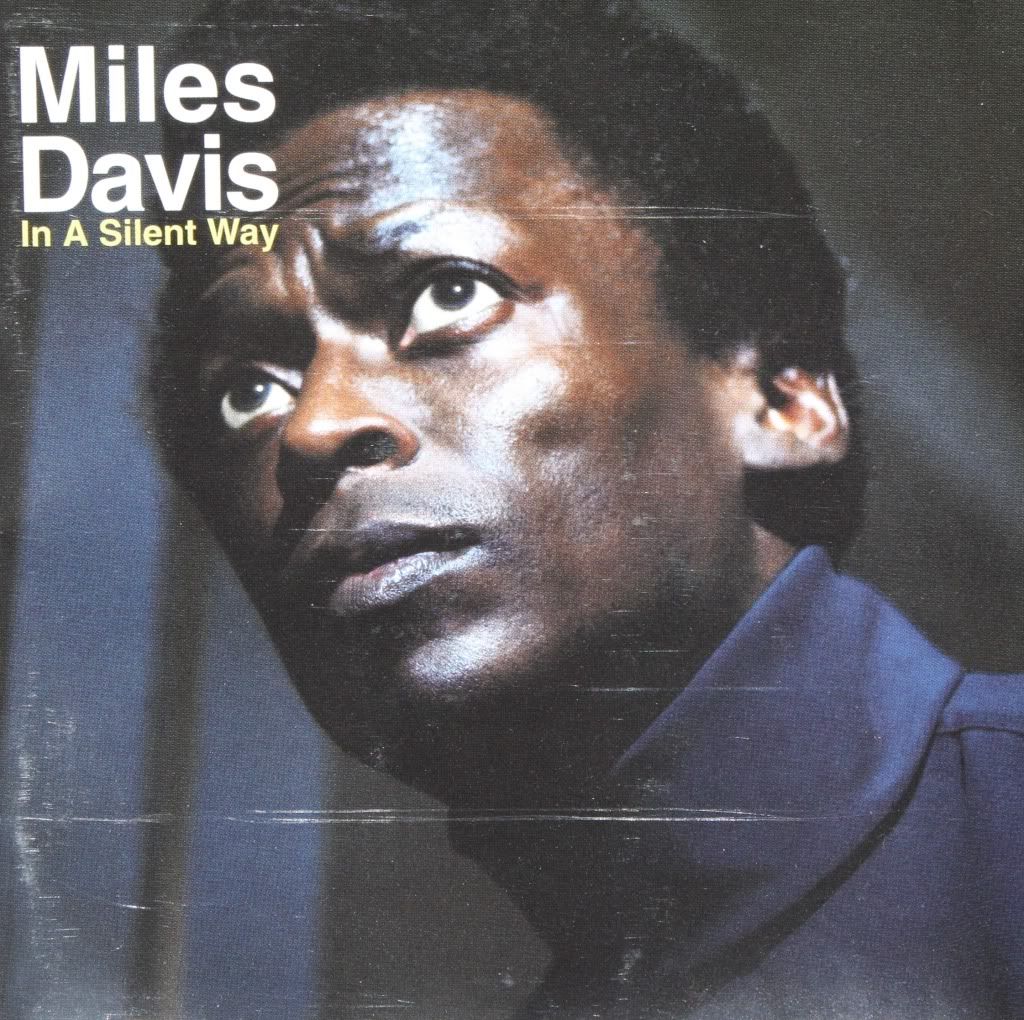

Miles Davis - In a Silent Way

From the intense turtleneck cover shot to the audacity of consisting of only two tracks to the brilliantly succinct poetry of the title (as in, "do that in a silent way" and when used like "I'm in a real bad way"), it's easy to see that In a Silent Way is a classic Miles Davis album. With a lineup that would become a virtual who's-who of jazz fusion music by the end of the 70's (including Chick Corea, Herbie Hancock, Tony Williams, Joe Zawinul, and John McLaughlin), the album is literally a first statement of the vocabulary that many other early fusion efforts reiterated close to verbatim.

From Hancock's (or is it Corea's--they both play electric piano) dissonant opening chord cluster to the last ringing guitar notes, the album is like a warm bath of pure tone. Historically, a lot is made both of Davis' unprecedented and extensive use of electric keyboards and electric guitar as well as his pioneering introduction of rock rhythms into the jazz idiom. Listening over 40 years later, when all of these things are commonplace, I'm struck--not with surprise at Davis' irreverent artistic choices, but more by a sense of how much better he did it than countless other followers who managed to turn fusion from an exciting and edgy novelty to a naughty word (much like "prog," hmmm...) in fewer than 10 years.

What's the secret? It's hard to say, but near the top of my list has got to be taste, variously on the parts of Davis as a bandleader, the rest of the players, and producer Teo Macero. As an avowed fan, I'll take the risk and say that I appreciate Miles Davis even more as a bandleader than I do as a player. All you have to do is look at the careers he helped start or further (from the first and second great quintets on through the 70's) to see that he had a keen ear for talent, an ability to properly employ his bandmates, and an uncanny ability to nurture them and propel them to successful, often visionary careers of their own. While most of the artists in this band weren't fresh (McLaughlin was practically unknown, though), Davis puts them to work with impeccable taste, fusing and contrasting two electric pianos, using organ as both a tonal and atmospheric device, slowing the guitar down in its statement of major melodies and laying out its full harmonic range, and employing an unbelievably great rhythm section (Dave Holland and Tony Williams) in some of the most boring and repetitive patterns seen in the history of jazz--because it's what the compositions need.

On the part of the players, infallible taste crops up again and again in their willingness to leave space for each other (after all, it's a pretty big band--show me footage of Davis from the 70's or 80's ever attempting to wring so much quietness out of such a large ensemble) and space for nothing at all. Players take relatively long breaks between phrases, allowing the timbral subtleties to contrast without competition, and the keys and especially the guitar manage to produce enough jaw-dropping fills that full-fledged solos seem unnecessary. Wayne Shorter's role on soprano saxophone, limited though it is, has got to be one of the most restrained and atypical soprano performances I've ever heard. For his part, Miles provides undeniable cool (even quoting [or self plagiarizing, depending on how generous you want to be] his landmark "So What" solo in "Shhh/Peaceful") as well as just a bit of speed when the energy ramps up. The entire performance, really, exudes an air of collective purpose that melds Davis' well-established cool with a sort of spare, breath-holding restrained energy--while few jazz albums even have a collective purpose, even fewer actually pull it off.

Likewise, Teo Macero's contributions to this (and numerous Davis albums to come) are integral to the album's success. While I feel it sort of breaks the final studio album's inimitable spell, the Complete In a Silent Way Sessions box set makes obvious the differences between the traditional ballad style and final album version of "In a Silent Way" (the song) as well as the longer jams and final versions that were "It's About That Time" and "Shhh/Peaceful," differences which seem like insurmountable gulfs. Macero's editing provides subtle but crisp breaks that punctuate the otherwise homogeneous extended tracks, especially within "Shhh/Peaceful" (listen for those lower-register electric piano riffs) and right before the "In A Silent Way" theme is repeated right at 15:35 in the second track--these moments of gentle juxtaposition, heretical as they may be to jazz's organic and spontaneous origins, are pure magic. While the entire album has been accused of not going anywhere (though I believe describing the music as ambient or even proto-ambient is a laughable proposition; let's not confuse a de-emphasis on obvious melody with a genre solely focused on exploring one--and only one--of music's many great characteristics), I think the beauty lies in the subtlety--crank up the sound to soak up those glorious analog keys and guitar, and by the time the crescendo in "It's About That Time" happens, you know that things are changing. I think Macero's editing is again crucial, since the songs--long though they are--use vaguely classical structures to state themes, travel elsewhere, then return.

Like I hear it is for many people, Miles Davis was one of the very first jazz artists that got me more interested in trying to understand and enjoy the genre. The more I explore avant-garde and free jazz, the more I realize that while those movements are aimed at stretching the expressive, compositional and pure sound aspects of jazz to the fullest extent, Davis never really went that direction and was almost always focused on jazz as a pop form. Now, both approaches are equally valid and I'm not saying "pop" as in lightweight, lowest-common-denominator or shallow, but rather as an ideal of accessibility and an attempt to acknowledge what the people are listening to. As he began to transcend the trappings of cool, modal and bop forms of jazz, Davis attempted to combining jazz with other forms of popular music, including rock, blues, R&B, funk, and folk music from around the world in effort to keep the genre evolving. While it worked brilliantly more than once for Davis and nearly as well for some others, it's debatable whether it was healthy for the genre's identity in the long run to continue attenuating its key characteristics and adding more and more generic content (much like what's happened to country music since the 70's). Stuffy historical observations aside, In a Silent Way remains a revelatory experience with every spin and a great jazz album for people who don't even like jazz.

Tuesday, August 16, 2011

Gentle Giant - In a Glass House

With at least five solid albums, a lineup full of virtuoso multi-instrumentalists and a totally unique sound, to me, Gentle Giant is a great band. While their counterpoint-focused arrangements and penchant for unsettling busy-ness and atonality were probably too sophisticated to garner the group mainstream success (even in the early 70's), looking across their discography it's clear that even in 1973 the band was aiming for a more commercial sound. While many people point at Octopus as their best (and it probably does the best job of fusing their more experimental side with a less dated sound and strong songs), In a Glass House is probably my favorite in their discography for its graceful first statement of the classic mid-70's Gentle Giant sound, its many memorable moments, and some of the strongest songs on any of their albums. Make no mistake, though--this is 70's prog, and there's little on this disc to make you forget.

In a lot of ways, Gentle Giant are like some weird progressive version of the Band--their verve is infectious as the band members swap vocals and trade around on something like 30 different instruments based on the needs of each song. Like many of the later Gentle Giant albums, In a Glass House is loosely based on the title's concept, which plays out generally in a set of songs that focuses inward on matters of psychological introspection and interpersonal relationships. While it's hardly a meticulously laid-out treatise, the themes add cohesion and the lyrics are always intriguing if sometimes inscrutable.

While the songs are mostly long (four of six are over seven minutes long), they're distinctly songs and feature compelling examples of the band's trademark fusion of rock, classical, folk and the occasional soul and funk elements. In addition to a good flow between rockers and quiet reflections, there are loads of great moments, like the gleefully atonal xylophone solo on the opener "The Runaway," which also manages to state themes of complex counterpoint, psychedelic and spacey vocal arrangements, hypnotic guitar riffs, and some great folky flute breakdowns. As always, the transitions are seamless and the music is anchored by a fat, funky bottom provided by the bass and drums. "An Inmate's Lullaby" features only percussion instruments and uses some great overlapping vocal production to enhance a first-person narration of a mental ward and the gray area that is "madness" (a classic theme in British music of the 60's and 70's).

"Way of Life" is maybe the least listenable track, with a slightly frantic opening riff, but it's certainly dynamic and a great example of how good the band is at juxtaposing Derek Shulman's ballsy lead vocals with Kerry Minnear's delicate vocals, which show up on a great pump organ section that emulates church music. "Experience" is more classic Gentle Giant, with lots of contrast between odd-metered violin/guitar riffs, medieval-sounding vocal harmonies and a simple repetitive bass riff. Gary Green's mid-song guitar solo, while not the proggiest thing on the album, is glorious for its razor-sharp tone, a perfect helping of slappy reverb, and the way it fits so well over the aforementioned bass riff. Similarly crushing is the heaviness of the main riff of "In a Glass House," which has both a flitting, jazzy opening section and a ballad in the previous song ("A Reunion") to make it sound even heavier and worthy of its place as the album-closer. While bands like Henry Cow employ a similar amount of counterpoint but focus on an edgier and more experimental brand of progressive music, it's hard to complain about how Gentle Giant manages to make such geeky music so catchy. They pursued this album's template with admirable success through The Power and the Glory, Free Hand, and Interview, but I think it was definitely at its freshest state here. Great album.

Saturday, August 13, 2011

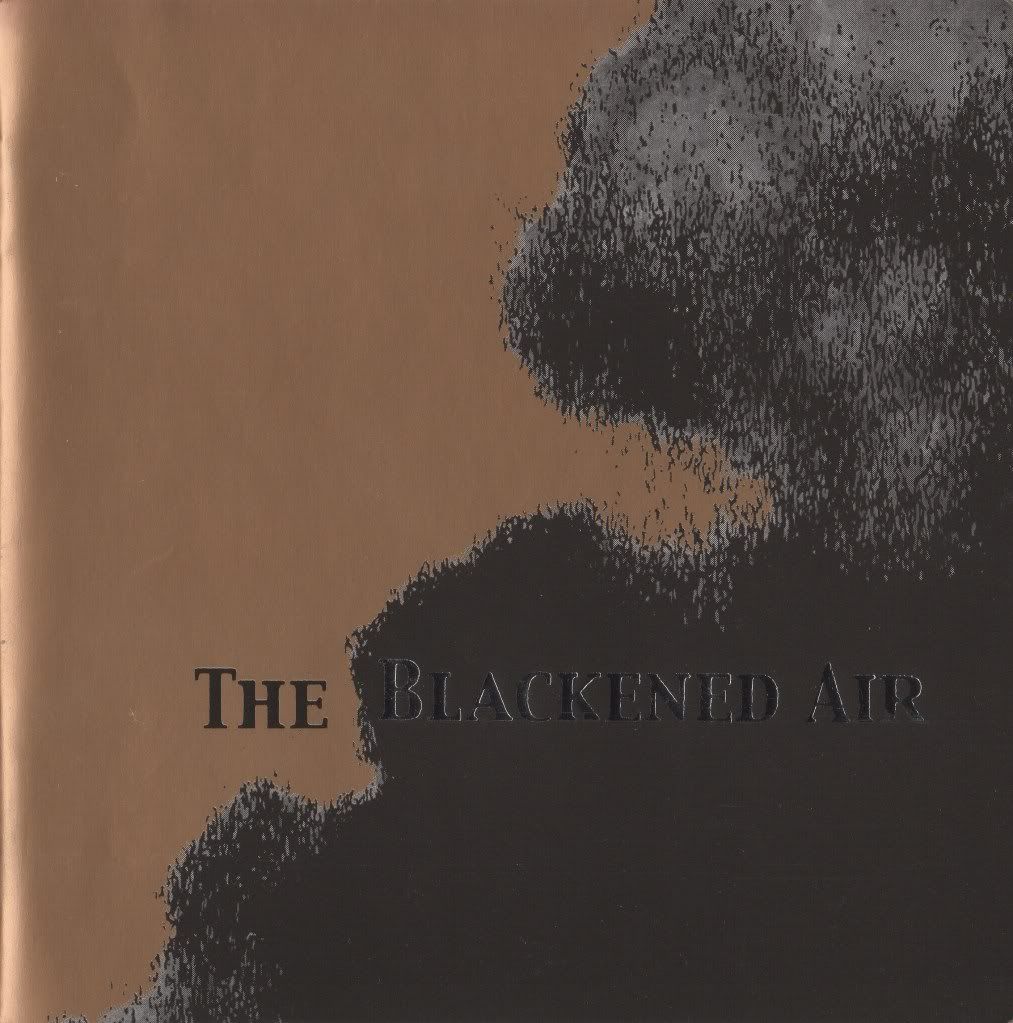

Nina Nastasia - The Blackened Air

I can think of few better examples of album art that evokes the sounds contained within than Nina Nastasia's 2002 sophomore effort, The Blackened Air. There's a smoky duskiness that's always prevalent in her music, lingering and diffuse like the on the cover. And yet, there's also a contrasting sort of autumnal warmth that takes the edges off her dark ruminations and the desolate moments she highlights in clock-stopping detail.

Nastasia seems to be a rarity in today's "Americana" landscape insofar as she's been doing this since the late 90's (well before the current fad took off) and there's very little artifice in her delivery and the sentiments expressed in her songs. Rather than affecting a fake southern accent on songs like the Appalachian-esque "Oh, My Stars," and the the twinkling "All For You," her wispy vocals tell the story with pure tone and no trace of a cheesy accent. The former is a great example of Nastasia's graceful songwriting--the song conjures a vibrant sense of the moment, describing the fall of an icicle before getting to the real subject, the discovery of and the narrator's father's pursuit of a peeping Tom in the night. Throughout The Blackened Air Nastasia proves particularly adept at spinning whole stories out of short moments. The ability to improve storytelling by leaving out details is one that not every songwriter can pull off, but Nastasia manages to successfully employ the technique to juxtapose a cemetery visit with memories of childhood games ("In the Graveyard"), evoke the irony and resentment of relationship subservience ("I Go With Him") and to blur the lines between external and internal antagonism (the delightfully dirge-y waltz, "Ugly Face").

Though a quick perusal of YouTube reveals that Nastasia's songs lose none of their power in a live setting, one of my favorite parts about this album is how well-done the arrangements are. The songs are loaded with cello, violin, musical saw, accordion, mandolin and the more traditional sounds of guitar, bass and drums. So much Americana I've heard treats strings like a novelty, but here they provide both atmosphere (probably the easiest thing to accomplish, especially with amateur string players), but also melody and harmony that accentuates Nastasia's spare but repetitive two- or three-note rhythm guitar phrases. The noise is glorious on the opener, "Run, All You..." when the barely audible opening gives way with a crash as Nastasia states the album's title with a forcefulness belied by her usual vocal delicacy. Sometimes they do both, as on the album's centerpiece and emotional nadir, "Ocean," where the the cello is variously a source of cacophony in the song's first crescendo, a gentle pizzicato companion to Nastasia's voice that builds into broad, deep strokes for the second crescendo, and a trove of texture for the uncertain aftermath that draws the song to a close.

Among Nastasia's growing discography, I like The Blackened Air maybe the best, since its occasional cacophonous darkness points the way to her next album's (Run to Ruin) more thorough examination of those textures while at the same time retaining the recognizable folk and country tropes that made her debut, Dogs, such an accessible introduction. I'm also always impressed by the brevity of Nastasia's songs--she packs so much into so little space by building her songs with gossamer threads. There's very little in the way of identifiable verse/chorus chunkiness, though those elements are often present. Though the album is quite thoroughly dark, there are moments of bright beauty and joyousness that certainly prevent a monochromatic mood. Though she's managed to keep a mostly cult-level profile despite 10+ years making music, I still think Nastasia is one of the most sophisticated songwriters working in her field, and a damn sight more inventive when it comes to artistic integrity and vision.

Nastasia seems to be a rarity in today's "Americana" landscape insofar as she's been doing this since the late 90's (well before the current fad took off) and there's very little artifice in her delivery and the sentiments expressed in her songs. Rather than affecting a fake southern accent on songs like the Appalachian-esque "Oh, My Stars," and the the twinkling "All For You," her wispy vocals tell the story with pure tone and no trace of a cheesy accent. The former is a great example of Nastasia's graceful songwriting--the song conjures a vibrant sense of the moment, describing the fall of an icicle before getting to the real subject, the discovery of and the narrator's father's pursuit of a peeping Tom in the night. Throughout The Blackened Air Nastasia proves particularly adept at spinning whole stories out of short moments. The ability to improve storytelling by leaving out details is one that not every songwriter can pull off, but Nastasia manages to successfully employ the technique to juxtapose a cemetery visit with memories of childhood games ("In the Graveyard"), evoke the irony and resentment of relationship subservience ("I Go With Him") and to blur the lines between external and internal antagonism (the delightfully dirge-y waltz, "Ugly Face").

Though a quick perusal of YouTube reveals that Nastasia's songs lose none of their power in a live setting, one of my favorite parts about this album is how well-done the arrangements are. The songs are loaded with cello, violin, musical saw, accordion, mandolin and the more traditional sounds of guitar, bass and drums. So much Americana I've heard treats strings like a novelty, but here they provide both atmosphere (probably the easiest thing to accomplish, especially with amateur string players), but also melody and harmony that accentuates Nastasia's spare but repetitive two- or three-note rhythm guitar phrases. The noise is glorious on the opener, "Run, All You..." when the barely audible opening gives way with a crash as Nastasia states the album's title with a forcefulness belied by her usual vocal delicacy. Sometimes they do both, as on the album's centerpiece and emotional nadir, "Ocean," where the the cello is variously a source of cacophony in the song's first crescendo, a gentle pizzicato companion to Nastasia's voice that builds into broad, deep strokes for the second crescendo, and a trove of texture for the uncertain aftermath that draws the song to a close.

Among Nastasia's growing discography, I like The Blackened Air maybe the best, since its occasional cacophonous darkness points the way to her next album's (Run to Ruin) more thorough examination of those textures while at the same time retaining the recognizable folk and country tropes that made her debut, Dogs, such an accessible introduction. I'm also always impressed by the brevity of Nastasia's songs--she packs so much into so little space by building her songs with gossamer threads. There's very little in the way of identifiable verse/chorus chunkiness, though those elements are often present. Though the album is quite thoroughly dark, there are moments of bright beauty and joyousness that certainly prevent a monochromatic mood. Though she's managed to keep a mostly cult-level profile despite 10+ years making music, I still think Nastasia is one of the most sophisticated songwriters working in her field, and a damn sight more inventive when it comes to artistic integrity and vision.

Monday, August 8, 2011

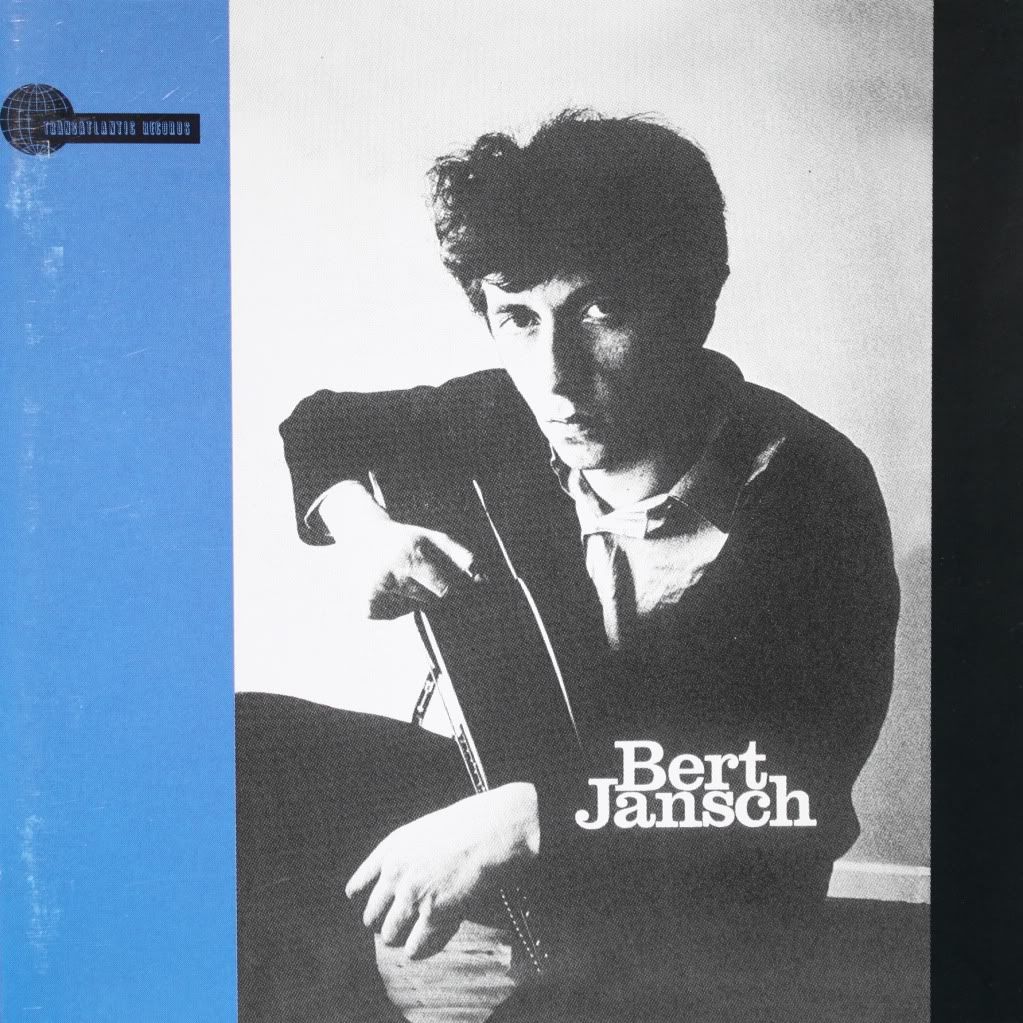

Bert Jansch - Bert Jansch

Bert Jansch is one of those figures whose legendary status in his field is easily justified but who never really succeeded in creating a categorically "great" album. In Jansch's case, the field is contemporary folk and especially acoustic fingerpicking. His prolific solo catalog and membership in The Pentangle (who arguably did record a few great albums), combined with his influence on many more notable guitar players add up to ample evidence for his reputation, but when it comes to selecting his best album, it's hard for me to find one that I feel is lacking in easily-identifiable flaws. His 1965 debut, though, is probably the best album to check out because it demonstrates most purely his personality, guitar abilities, interests (or lack thereof) as a songwriter, and his unique role in the 60's British folk revival.

Since it seems to be the number one critical talking point regarding this album, you probably already know that part of this album's mystique stems from the fact that it was recorded in a friend's flat on a borrowed guitar. Other than the fact that it actually sounds pretty good, considering, I think it speaks to Bert's abilities as a performer that the thing turned out so well--he makes nary a mistake in his playing, and it's easy to see how, in 1965 England, he was something of a rarity insofar as he was a folk(ish) singer who was actually quite capable at playing his instrument. Though many fans might be unaware that Davy Graham had already set this precedent at least a couple of years earlier, Jansch easily sits as one of the other firsts alongside future collaborator John Renbourn. Unlike Graham and many of the other young British people getting interested in folk music at the time, Jansch was one of the first to become recognized for his original songs; this pioneering shift from folk to singer/songwriter-contemporary folk is probably one of Jansch's most significant accomplishments.

As important as his debut was, listening in retrospect there are few really great songs on this album. The opening track, "Strolling Down the Highway" is one of them--Jansch's rough vocals sound great in unison with his string bends as he describes his rambling lifestyle and ironically mentions the suspicion with which he's treated by the straight-laced general public. "Needle of Death," notable for its unflinching directness (which overcomes one of the album's least interesting guitar arrangements and some awkward lyrical flow), is the best-known song on the album. "Do You Hear Me Now?" is pretty good too, raising up some counterculture fire that's absent elsewhere on the album. I know that some people don't cotton to Jansch's rough-hewn vocal style, but I actually don't mind it, considering the album's lo-fi vibe. He's rarely off-key and musters a decent vibrato at places, and when the music's like this, I'd prefer some roughness to immaculate perfection. In other places, Jansch seems content to tout the virtues and drawbacks of his rambling lifestyle through considerably less interesting songwriting, as on "Rambling's Going To Be the Death of Me," "Running From Home," and "Oh How Your Love Is Strong," where a rather unsympathetic narrator tries to explain to the mother of his child that he just has to keep his freedom. Then there's the confused "I Have No Time," a dark, cautionary piece that can't decide if it's about social inequality, hippie ideals or war. Despite the lack of vision in the songwriting department, though, Jansch's guitar is always a pleasure to hear.

Whenever I revisit this album, what strikes me most is how great the short instrumental tracks are. While Jansch sticks to pretty standard picking patterns on the vocal songs, the instrumentals show quite a bit of range in mood and Jansch stretches out in his playing style quite a bit more. "Smokey River" has a great sing-song melody for an opener and closer and the main body of the song rests on a chromatic figure punctuated by lots of gently dissonant polyphony in the high strings. It's easy to see that self-professed Jansch devotees like Roy Harper were listening closely; this piece is specifically reminiscent of Harper's own "Blackpool" from his debut, still a year to come. The whimsical "Finches" features some excellent syncopation surrounding an ascending figure, while "Veronica" and "Alice's Wonderland" flirt with a minor jazz feel. Finally, the instrumentals round off with two Davy Graham tributes--the single-note pounder "Casbah," which is quite obviously indebted to Graham's jaw-dropping arrangement of "Better Git In Your Soul," and Graham's own "Angie" [sic], of which Jansch produces a fine reading. Though I've heard Martin Carthy complain that Jansch has never played the song correctly, I find his hammer-ons and bursts of percussive strumming make it a lively and fresh interpretation.

Though Jansch's debut is far from perfect, it's always a pleasure to listen to. As a guitar player, it's also hard not to be inspired after hearing the man explore the possibilities of his instrument with such apparent ease.

Here's a great recent interview with Jansch that touches on his debut and Davy Graham's influence.

Friday, August 5, 2011

Egg - The Civil Surface

The sound of a ticking metronome opens Egg's third and final album, 1974's The Civil Surface. I don't think there's any better sound to introduce a band like Egg, whose music is probably the most classically-influenced of all the Canterbury bands and is typified by Mont Campbell's precise, intricate compositions that are filled in by Dave Stewart's interweaving organ and keyboard parts and driven by Clive Brooks' undeniably exact skills at the drum kit. The Civil Surface is really more of a reunion album for Egg (not to be confused with newer group, The Egg), as the group had broken up in 1972--luckily for us, they had another album in them and here develop the sound of their first two albums even further.

Being a reunion album, The Civil Surface is a bit of a fractured collection. Therein lies the main stumbling block regarding my ability to enjoy Egg--they present some of the most interesting and "out" ideas of any of the Canterbury (or any other progressive bands, for that matter), but when it comes to crafting a cohesive and really great album, they were never really able to make it happen. The ideas really do reach rarefied heights, though. The aforementioned opener, "Germ Patrol" is perhaps most typical of the group's overall career sound, with plenty of Canterbury fuzz organ and bass, jazz harmony and ear-surprising twists. It's on this track I most notice a common complaint with The Civil Surface--the drums are mixed extremely loudly, and it's especially painful when Brooks goes for the high-hat, with lots of sibilance that can be really sharp and hard on the ears. Because of this, the album doesn't really sound good on a lot of sound systems (especially ones prone to treble-y sound), and the more you push the volume to discern the compositional intricacies, the more the drums get in the way. The song plays effectively with additive rhythms and builds on its somewhat anonymous melody, though, and features nice clarinet and bassoon from Henry Cow guests Tim Hodgkinson and Lindsay Cooper, respectively, and some signature french horn from Campbell. This style reprises on the confusingly-titled mid-album "Prelude," which also features wordless female vocals reminiscent of those which would later appear on related acts Hatfield and the North and National Health.

The album's crowning achievement is undoubtedly "Enneagram," which Mont Campbell supposedly composed in response to composer Aaron Copland's criticism that his "Long Piece" (from The Polite Force) was merely music of repetitions and didn't develop. Campbell certainly took Copland's words to heart--over its 9 minutes, "Enneagram" develops Egg's tricky rhythms to their fullest, alternating between driving hard, fuzzed-out riffs and spacey sections where Stewart's keys flitter away with echo and the cymbals provide a backdrop for Campbell's bass runs. The song's rousing conclusion fuses heavy toms with stuttering organ and bass unison. It's really interesting to hear Dave Stewart's keyboard work in the midst of the 70's; though the compositions are mostly Campbell's, there are keyboard moments that recall both the gentle jazzy interludes of previous band Khan as well as crisp contrapuntal figures that predict breaks that show up later in National Health and Hatfield and the North. Though that style dominates here, I think it displays Stewart's abilities to play to different styles but also forge a distinctive style of his own when the time came for his compositions to dominate.

As for the rest of the set, there's material that echoes Egg's earlier work ("Wring Out the Ground Loosely Now"), featuring what are probably Campbell's weakest vocals to date and some mainly textural guitar from Gong and future solo star Steve Hillage. Compared musically and lyrically with "Contrasong" from The Polite Force, it doesn't hold up so well--depending on how you look at it, the vocals either add variety to or awkwardly interrupt a mostly-instrumental album. There's also plenty of material exhibiting some modern classical vibes, like the interesting and blithely-plodding "Nearch" which joyfully experiments with continually-increasing amounts of silence, and two wind quartets, which only feature Campbell from the Egg lineup. To my ears, the sprightly first quartet ironically echoes some of Copland's more accessible works, albeit with a little more dissonance, and the second experiments more with longer-sustained notes and a sort of rocking eighth-note rhythmic figure. The quartets are good, in my opinion, but if you came to Egg looking for their more rocking tendencies, I can see how you might find them irrelevant and cluttering. As I mentioned earlier, despite a wealth of creative ideas, the album can't seem to weave its variety into a really good flow. Still, I manage to enjoy it quite a bit every time I hear it!

Thinking about Egg in the context of their whole discography and the Canterbury scene in general, it seems like their strengths lie more in their rhythmic and contrapuntal pursuits rather than their melodies--even the best songs here are difficult to recall melodically, in part due to the fact that only bass and keyboards contribute to the melodic statements. Though melody probably wasn't on top of the list of the band's intentions, I can't help feeling that this contributes in a mildly negative way to their overall accessibility--but hey, we're talking about the Canterbury scene already, so there's no need to worry about billboard charts! Judging by his recent interviews on the BBC's progressive rock documentary and on blog friend It's Psychedelic Baby's recent interview, Mont Campbell is fairly bitter that he wasn't allowed to fully flower as a composer and musician because the music business wasn't nurturing enough. It's the sad truth, but three albums released on fairly large labels is a whole lot better than similar artists are getting these days! Sometimes we just have to nurture ourselves.

Tuesday, August 2, 2011

AMM - The Crypt: 12th June 1968

It's been a while since my last AMM review--with The Crypt we move to the primary album outside of AMM's 1967 debut AMMMusic that points to the foundations of their immortality in the world of avant-garde music. Despite my passion for AMM and other free improvisation and avant-garde groups, writing about music like this is at once easier and more difficult than writing about traditional styles or genres. Easier because the lack of structure and outrageously long tracks usually demand considerably less writing, since there aren't any lyrics or a large number of individual "songs" to describe and evaluate, and more difficult because the music bears little relation to most traditional music and the vocabulary used to describe such music is of little use. It may or may not help to reference an earlier essay in which I tried to articulate some aesthetic concepts that more accurately apply to music like this. Either way, I'll do my best to describe in a meaningful just what it is that I enjoy in The Crypt: 12th June 1968.

By this time in the collective's history, the core group of Eddie Prévost (percussion), Lou Gare (saxophone), Keith Rowe (guitar/transistor radio) and Cornelius Cardew (cello/piano) were augmented by percussionist Christopher Hobbs; absent from the AMMMusic lineup is multi-instrumentalist Laurence Sheaff. It's not my primary focus in these reviews to chronicle groups' membership and instrumental roles--the main reason I mention it is because, when the music starts, there's really no way to discern who's making which sound and what the audible instruments even are. The concert begins with a couple of seconds of high-pitched feedback, a couple of seconds of dissonance not unlike the sound of an orchestra tuning, and then around the seven second mark, a thick howl is undeniably the center of attention, as it will be for over a half hour of this 90-minute set. "Noise"-haters, please exit through the wings--I'm not here to argue about whether or not this is "noise" or music, nor am I here to apologize for the characteristics of the sounds contained here; I wholly understand that most people probably won't enjoy how this sounds, but the validity of the assertion that someone can and does enjoy this isn't up for debate. Not that the two are mutually exclusive, but one great thing about being an AMM fan compared with loving Captain Beefheart and Trout Mask Replica is, for the most part, you don't have a chorus of sanctimonious people telling you that you're lying about liking how it sounds--even fewer people give a shit about AMM.

When I think about The Crypt, it's this howling sound is the first thing that comes to mind. The sustained collective sound is the most purposeful study of timbre I can call to mind; it's not the note or pitch that attracts attention, but the quality of the sound. Hearing the undulating screech as the layered instruments blend and enfold only to compete again, the descriptors that come to mind pertain to the sense of touch--rasping roughness drags across the seconds, and a certain viscosity seems to govern the pace with which each instrument's sound slowly evolves across time, and the primal sense of vibration happening between the different sound sources shifts at what seems like a glacial pace between the miniature warbles of dissonance to the earthquake rattling of flagrantly high volume. Also particularly noticeable are definite spatial feelings--the music sounds at some points like it's expanding omni-directionally into an endless void and at other times it conjures a feeling of rapidly speeding through a narrow tunnel. In one sense, the collective sound is liquid in the way it seems to move within itself slowly and naturally, but there's simultaneously a dryness to the collective sound, as if every sound source is being scraped to produce the sound. When it comes to declaring that this is "good" (implying that there's similar music that isn't), my first instinct is to say that it's the collectivity that elevates this music above the quality of so-called "noise rock" for me. It's likely that Keith Rowe's prepared guitar and electronics account for the backbone of the sound, but without the shadings and constant flux of the other players (keep in mind there's a saxophone, percussion, cello and piano contributing, though, as the liner notes so eloquently state, "It was not uncommon for the musician to wonder who or what was creating a particular sound, stop playing, and discover that it was he himself who had been responsible") that separates the subtlety of this sound from just a couple of guys seeing how loud they can get their distorted guitars to feedback. Though the sound is ultimately inseparable and cohesive, all of the players' personalities are perceptible to an extent; like the best free jazz that came before free improvisation, each person leaves enough space for the others.

The dynamics of the epic howl ebb and flow past the half-hour point, at which time the proceedings become significantly quieter. It's pretty surprising, actually, how similarly the second disc sounds to the AMM of the 90's and 00's; the contributions of each member are quite a bit more audible, though it's not a lot easier to discern what the instruments are (percussion aside). Interestingly, the droning of the first half is still present, but in an attenuated form--it's almost like a different version of the same thing, more distant or more spacious. In this way, part of the magic of The Crypt is the way in which it plays with the experience of time. The music could easily be summed up thus: "A really loud screechy howling noise, then more quieter droning with a bit more space and silence with some intermittent crescendos." Thing is, it takes 90 minutes for all of that to happen--it's like the shriek of a hawk slowed to 5,000 times the original length of the cry. If you're not paying attention, time disappears and a limitless pool of sound is the only thing there is. I can only imagine how awe-inspiring it must have been to experience the concert live, in the moment, without the ability to replay the recording over and over. As anathema as recordings are to the AMM school of improvisation, albums like The Crypt bear repeated listening remarkably well. Beholding the sounds the group produces is like turning over a crystal in front of your eyes--there are innumerable intricacies and crannies to be found. There's also something to be said for the cathartic effect produced by the band's immediate sonic assault and the lengthy but punctuated denouement.

There are AMM albums with more variety, more changes in dynamics and diversity in instrument color and perhaps more relatable musical structures, but I'd be hard pressed to find one that's more intense or one that goes any deeper in pursuit of a single idea than The Crypt. In closing, I take enjoyment in recollecting the first time I realized that the track titles on this (as well as some on AMMMusic) come from my favorite Daoist text, and a major influence on In Not-Even-Anything Land, the Zhuangzi (the liner notes quote the part of the text that "Box Elder" is based on, though they call him Kwang-sze). Strangely enough I leaned heavily on the Zhuangzi when first attempting to wrap my head around music like AMM and Henry Cow's free improvisation--the text's exhortations to strip away preconceptions in pursuit of the gnarled beauty that lies in spontaneity and the natural state of things were key to my understanding of the music. Nice to hear that I'm not the only person who thinks the Zhuangzi might have something useful to say about music appreciation.

CD available here.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)