Thursday, June 30, 2011

T2 - It'll All Work Out In Boomland

If you're reading this, there's a good chance you already know that a big part of the allure of hunting through obscure albums from 40+ years ago is the chance of finding buried treasure--a great album or group that for whatever reason never achieved success in its day but deserved much more attention than it ever got. Now that we've got the internet, there are numerous resources (review aggregates like allmusic, user-generated databases like Rate Your Music, helpful product reviews on Amazon, and any number of great blogs) dedicated to spreading the word about great, sometimes non-commercial music. Thing is, the same basic rules apply to these sources that apply to the mainstream media's coverage of commercially-successful music--there's hype surrounding some artists, reviews aren't always well-written or unbiased, and aficionados of a certain genre can sometimes be a little hyperbolic when describing how good an album might be in a general sense. Sometimes artists are hyped for the simple reason that original vinyl copies of their albums have always been scarce and sell between record collectors for huge sums of money--often times irrespective of the actual quality of the music. None of these rules are hard-and-fast, though, and like always we have to use our own tastes and personal preferences to decide if something is buried treasure or not--even if a bunch of people say it's great.

I came across T2's sole 70's release, It'll All Work Out In Boomland, while on the hunt for some fresh, good heavy, psychedelic and progressive rock, finding it heavily lauded by a number of sources. Naturally, my expectations were pretty high after hearing a lot of praise for this album, and I can firmly say that it doesn't meet them. The album consists of four tracks (ah, the 70's), the first of which is a fairly uptempo rocker ("Moving in Circles") with a jazzy guitar riff. While it's not an inauspicious start for the album, there's nothing to distinguish the mildly dissonant guitar lines from any number of similar 70's bands that didn't make it big--melody and the ability to compose catchy riffs are things that you either have a special knack for or you don't, and while the riffs on this song certainly rock and are pleasant to listen to, it's easy for me to hear why they didn't stick out to 1970 listeners.

Another element on which hard rock stands or falls (for my tastes) is vocals--so many obscure bands from the 70's wear their lead singers like albatrosses around their necks. T2's lead vocalist can certainly sing on-key and not unpleasantly, but his voice sounds like any number of generic rock singers of the era and it pretty much never rises to a level of aggressiveness that matches that of the music's high points. The lyrics are vague but not compelling enough to provoke any sense of mystery or closer listening. Again, it's easy to hear how singers with more distinctive vocal styles achieved more success in the hard rock genre.

The center of the album is made up of two ballads--the first, the mellow, and jazzy acoustic guitar/piano-driven "J.L.T." never really takes off, though there's a cool odd-metered piano/mellotron riff at the end. "No More White Horses," more of a power ballad, is probably the album's best track from a songwriting perspective, plodding along into a dramatic buildup with some electric guitar shredding and a majestic trumpet melody. The side-long "Morning" closes the album, beginning downbeat (yet again) and building into some riffing that recalls the first track, as well as some pretty satisfying interplay including the bass and drums. For an epic, it's fairly well-constructed, with some loud/soft/loud alternations and a pretty great "Whyyyyyyyyyy" vocal refrain, though I'm not sure the ideas presented really warrant over 21 minutes.

After my initial disappointment, this album has incrementally grown on me--in spite of its generic nature, there's surely some craftsmanship at play, and it's certainly better than quite a few obscure albums in its genre. Part of my disappointment lies in the style of the music--though it's "hard psych," most of the tempos are almost maddeningly slow, even if there is eventually some heaviness to be found--I prefer my hard rock/proto-metal to have quite a bit more energy, though changes in dynamics are always welcome. I also prefer a lot more in the way of good guitar hooks and riffs--the soloing here is ok if a bit limited in terms of different musical ideas presented, but most of the time the mix is a lot of chordal sound without much identifiable melodic substance holding it together or giving it direction. As I mentioned before, the riffs that are actually here aren't particularly distinctive or interesting. I'm much more likely to reach for something like Captain Beyond, which swiftly and relentlessly pursues a wealth of compelling ideas with an uncluttered and forceful guitar sound and much better vocals, or something like High Tide's Sea Shanties (more on that one later), which is heavy to an ungodly degree without sacrificing energy or a clear sense of melody--both of which are much more satisfyingly progressive, rather than simply taking cues from prog's tendency to sprawl (which is just about the sum of T2's connection to progressive ideals).

When it comes to searching for hidden gems, you can't win 'em all--this album's attempt at an anthemic sound didn't really strike me as particularly heavy, progressive or psychedelic, but I can see why people who are really into hard psych, etc., might be able to get behind it--that's about the only listener to whom I'd recommend this album. Since it's not my #1 genre, I have a much lower tolerance for generic sounds than I would with, say, something from the Canterbury scene or avant-progressive rock. As it stands, I can leaven the majority opinion with my observations and try and help like-minded listeners avoid disappointment.

This album is out-of-print, but you can find it here.

Tuesday, June 28, 2011

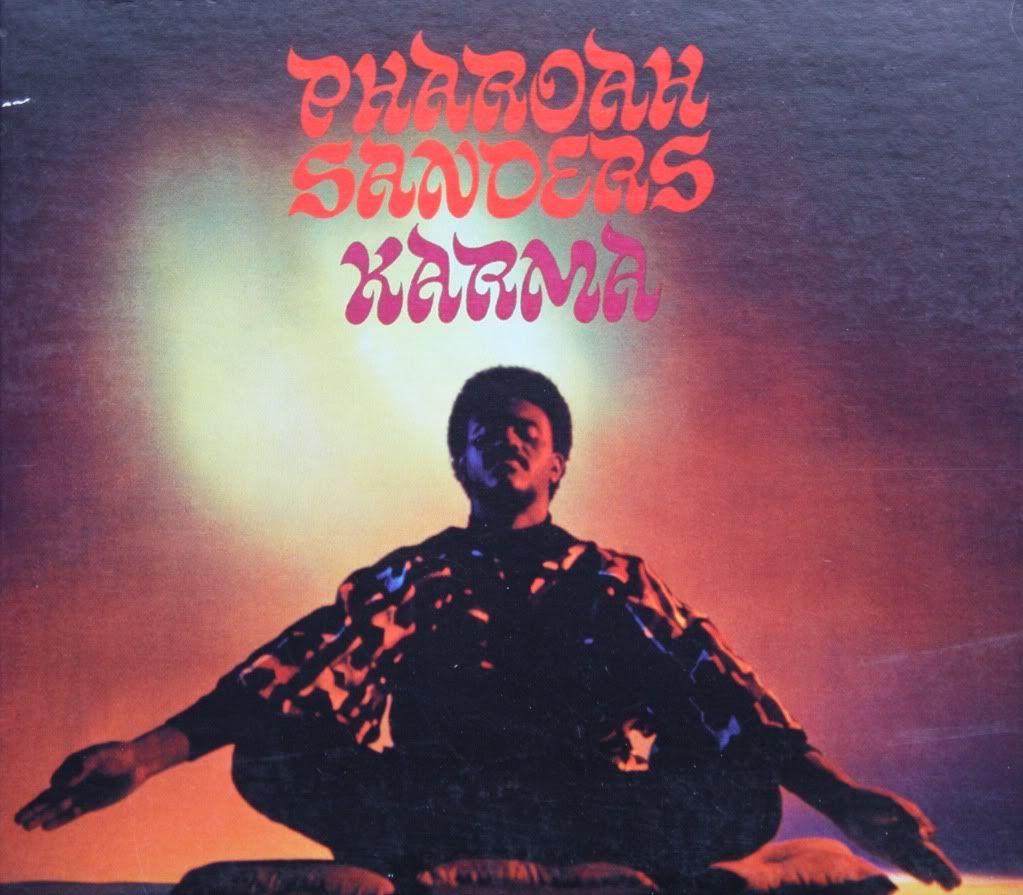

Pharoah Sanders - Karma

In my nascent explorations of avant-garde and free jazz I've heard Pharoah Sanders' name numerous times (he first achieved notoriety playing tenor in John Coltrane's combos and influenced Coltrane's move to free jazz), and I've seen Karma, his 1969 breakthrough solo album, near or at the top of quite a few lists of the best free jazz albums. Unfortunately, though, personal tastes don't always jive with popularity, and this album stands as my first big free jazz disappointment.

There are so many flaws and annoyances that easily come to my mind, from the obvious (atrocious lyrics--hell, the fact that it even has vocals at all) to the less obvious (the fact that there's almost no harmonic development over the course of a half hour, and the fact that Sanders' saxophone, which sounded so blistering on John Coltrane's Ascension, occasionally comes dangerously close to sounding like SNL opening credits/softcore porn soundtrack) that I couldn't even imagine calling this one of the best albums of the free jazz movements. The first time I listened to "The Creator Has A Master Plan" and Leon Thomas started going "Yeah yeah yeah yeah yeah..." I was thinking, "Oh no, is that what this is about?" The lyrics, few though they are, are among the worst of the era for their painfully broad, facile peace n' love message, and they get even worse on "Colors," where the hoped-against happens again--"yellow....purple...." Is he really going to sing-list all of the colors as an illustration of how great god is? Yes, he is. And then there's the wordless vocal soloing--while I don't really mind Thomas' yodel phrasing, his improvisation here is a perfect example of why I have yet to be satisfied by a vocalist in a group improvisational setting--the lines he sings are the kind of generic, simplistic soul runs that any average music listener would likely attempt if told to sing a solo over this music. If this album is supposed to be some sort of pinnacle of free jazz--a genre supposedly anchored on unbridled freedom of expression, especially during soloing, then this sort of repetitive, rudimentary technique just comes across as middling. Let me put it this way--if a saxophone (even with Pharoah's tone) played the notes that Thomas sings, it'd probably be lambasted as one of the most boring solos ever laid to tape.

Ok, so the vocals are a major detractor. Take them away, and what do we have? Well, for the most part, we've got two chords for over a half hour's worth of music. That's dangerous territory--with a harmonic compositional structure that lazy, you've got to provide some variation in other ways. Miles Davis would do it the same year on In a Silent Way by adding and subtracting instruments, adding and removing subtle repeating riffs and themes, and allowing the energy to gently ebb and flow, then in 1972 he'd perfect the technique with On The Corner's merry-go-round of instruments, textures and rhythmic shadings. Here Sanders offers a mildly dynamic development with the percussion, which is one of the biggest draws of the album--it's definitely a thick sound, and when things ramp up around the 18-19 minute mark, it gets exciting. However, the piano and bass are both pretty rigid, and other than Pharoah's saxophone we have nothing to keep things fresh for around 20 minutes of the album. Other than the borderline cheesy sax sound (Sanders can't really be blamed too much for how much his sound influenced much worse soft jazz artists to come in the past 40 years), the minor-key opening flourish offers a change in texture and mood, and again around 11 minutes. So, for structure and development, we have to be satisfied with a lot of repetition and a general energy buildup that reaches a series of intermediary peaks before really topping out around the 20 minute mark--and make no mistake, this album exudes structure, which is disappointing considering its prized place representing a jazz movement that moved continually away from structure; I can't help feeling that there simply isn't enough compositional substance there for track's length and that an opportunity to make a much more interesting backbone for Sanders' soloing was missed in a big way. To be fair, the noisy, atonal section that happens from about 20-25 minutes is pretty great--all kinds of cacophony and the Sanders soloing I had assumed would be the centerpiece of much more of the album. The crescendo paces itself (what else could it do in a 32 minute song), and for that reason it's pretty effective.

Really, Sanders shines throughout with his thick timbre, trilling and melodicism, but it's a far cry from the crazy religious expression some descriptions would have you believe. Instead of something other, we get something mostly familiar and only occasionally rapturous--for the most part telling us how great god is rather than showing us. Though the resulting music's mainstream approachability won Sanders some much-deserved popularity and success, I think it falls far short of what the free jazz movement has to offer in terms of spirit, theoretical development, and actual other-worldliness. Can't win 'em all.

Decide for yourself and get it here

Friday, June 24, 2011

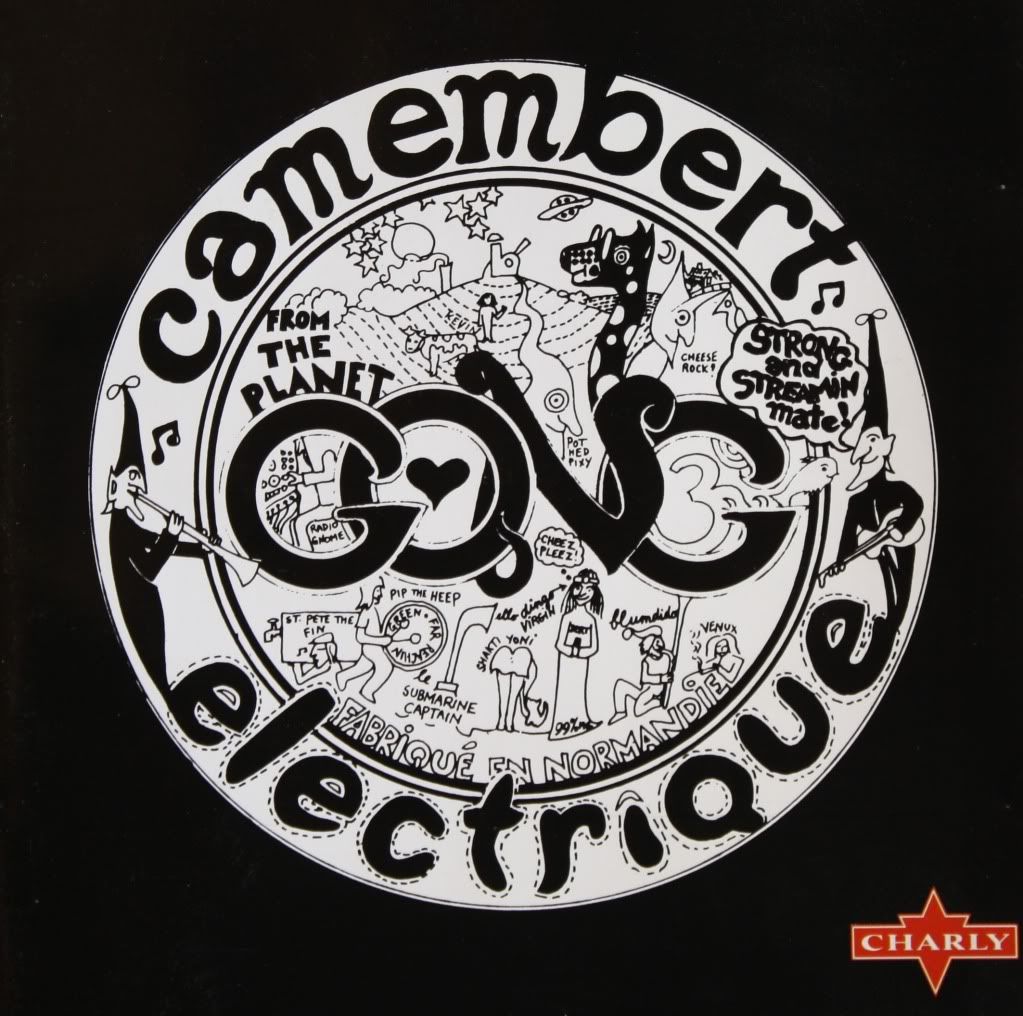

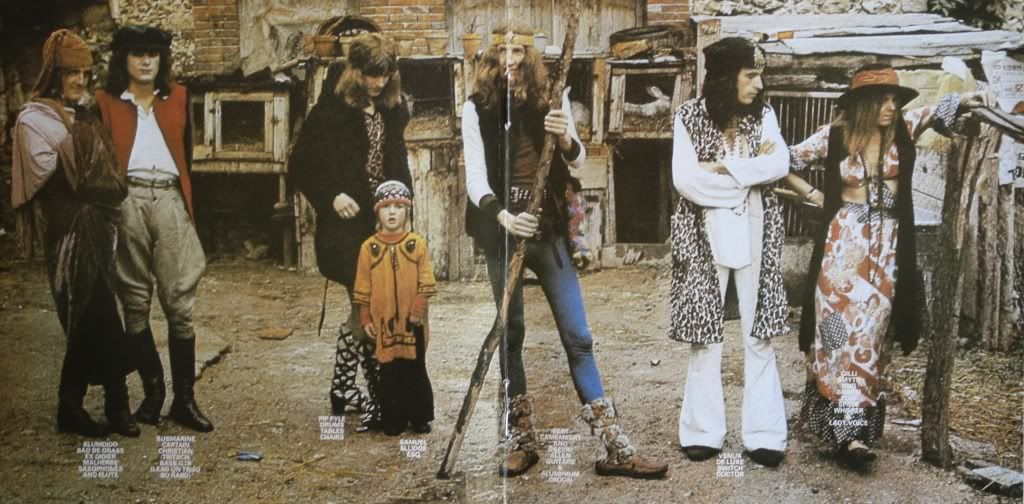

Gong - Camembert Electrique

Back to the Canterbury scene, but certainly not too far of a step away from free jazz or even RIO, here we've got one of the all-time great Canterbury albums and one of the most frenetic psychedelic rock albums of the early 70's. Even though he's not British, Aussie Gong bandleader Daevid Allen was a member of that most embryonic of Canterbury groups--The Soft Machine--which, along with other proto-Canterbury group The Wilde Flowers, was at one time home to members of most of the scene's later core bands. If ever there was a hippie, it would be Daevid Allen--he was famously refused reentry into the UK when attempting to return from Europe because of overstaying his visa on a previous trip, so he remained in Europe (mostly France) and formed Gong. It's for this reason that Gong is one of the most (if not the most) international of the original Canterbury bands.

Although Cambembert Electrique isn't the Gong debut (that honor goes to 1970's Magick Brother), it's undeniably the beginning of what most people consider the classic form of Gong--the one that concerns itself with Allen's hippie mystical and anti-establishment vision shrouded in mythology of teapots, Pothead Pixies and mythical planets, all displayed over some of the craziest jazz-influenced psychedelic music to be heard in the entire era. The story of the planet Gong is first broached in the sound-effect heavy opening introductory snipped voiced by the "Radio Gnome"--from there on out, though, the album is a nearly nonstop barrage of weirdness, humor, noise, rock and jazz that knows no equal--in the Gong discography and elsewhere.

"You Can't Kill Me" offers a pretty solid template for the album--Allen's winding but catchy compositions feature a lot of repeating figures and ostinati, looping rhythms and noise, while the lyrics hilariously toy with ideas of reincarnation and karma, while his partner Gilli Smyth contributes heavily-reverbed high-pitched moans, groans and what became known as "space whispers." Though on first listen this music might sound like utter chaos (well, it is chaotic, but not necessarily utterly), closer attention reveals an almost punk rock-like attitude supplemented by Didier Malherbe (distinctly "French" saxophone style) and Pip Pyle (unparalleled prowess on the drum kit, later to become one of the most experienced Canterbury journeymen) both of whom seem to have no difficulty negotiating Allen's compositions and their innumerable and quickly-transitioning ideas. Though the tumultuous Gong lineup later featured the more-lauded guitar hero Steve Hillage on lead guitar, I find Allen's guitar style particularly impressive for its audacity (just listen to the noise he conjures up on "You Can't Kill Me").

The album continues to plow an increasingly eclectic furrow with the organ-driven music hall "I've Been Stoned Before," where Allen goes from comical farce to sounding like he's going to shred his vocal chords in torment in just about 2 1/2 minutes. "Mr. Long Shanks" (see above video) transistions from gleeful carnival jazz rock ("The man in the parlor/you know what he's after") to a Gilli Smyth space whisper tour-de-force at its halfway point, while "I Am Your Animal" finds the female vocalist projecting a more aggressive (even x-rated) performance over Allen's spiky repeated riff, which morphs into a rapid-fire vocal barrage that ends with Allen madly yelling about licking the moon.

After a couple of sound collage interludes ("Tu veux un Camembert?") the band returns with the forward-looking (to later Gong albums) "Fohat Digs Holes in Space," which spins an atmosphere out of Allen's "glissando" slide guitar--the part when he seamlessly drops from the eerie high register into the midrange before 40 seconds is breathtaking. I'm not sure if glissando is really the correct word for the playing style, but that's what Gong fans have decided to call it--anyway, it's that echoey spacey sound that starts about 30 seconds in. The song's eventual rock riff is one of the album's catchiest, with Allen extolling some beat-cum-hippie poetry ("mirror mirror, on the wall, who's the biggest fool of all?") before another overdriven sax and lead guitar breakdown. The beginning of "And You Tried So Hard" is the closest thing to folk rock to be found on the album, though it quickly weirds itself out with more Gong flavor. The album closes just as powerfully as it opened with "Tropical Fish"--one of the band's most effective mechanisms is doubling the melodies on guitar and sax for a stabbing effect--with a heaping handful of bizarre riffs and lyrics ("seem like a typical witch to me/seem like a tropical fish to me"), a spaced-out interstellar desert in the middle ("I couldn't believe my eyes....") and closing with the almost martial invocation of the moon goddess, "Selene," and a recapitulation of the album's earlier machine-gun lyrical themes. The Radio Gnome returns to remind you that the ride's only just beginning, and you'd better believe him.

Although the full on Gong mythology isn't in narrative form here, the lyrical themes set the scene for the epic Radio Gnome Trilogy to come. Though Gong may have equaled the fun, trippiness and quality and ideological resourcefulness found here on later albums, they did it from a spacier angle, and sadly this album is in many ways one-of-a-kind with its energy, barrage of ideas, and noisy edginess. It manages to incorporate a lot of jazz influence without committing to long-form jazzy passages (like so many later groups, including Gong would do) by radically changing from idea to idea in short periods of time. Their arrangement style here is one that was certainly emulated by later Canterbury bands, and it's easy to tell that Allen's association with Robert Wyatt and Kevin Ayers was a mutually-enriching one; his idiosyncratic sense of humor obviously influenced to a large extent the sense of whimsy and insubordination prevalent in a lot of the Canterbury scene's later music. My only complaint with the Charly CD reissue of this album is sound, which is quiet, treble-heavy and not as full as I imagine it should be. Let's hope for a good remaster.

Until then, you can get it here on CD or MP3

Wednesday, June 22, 2011

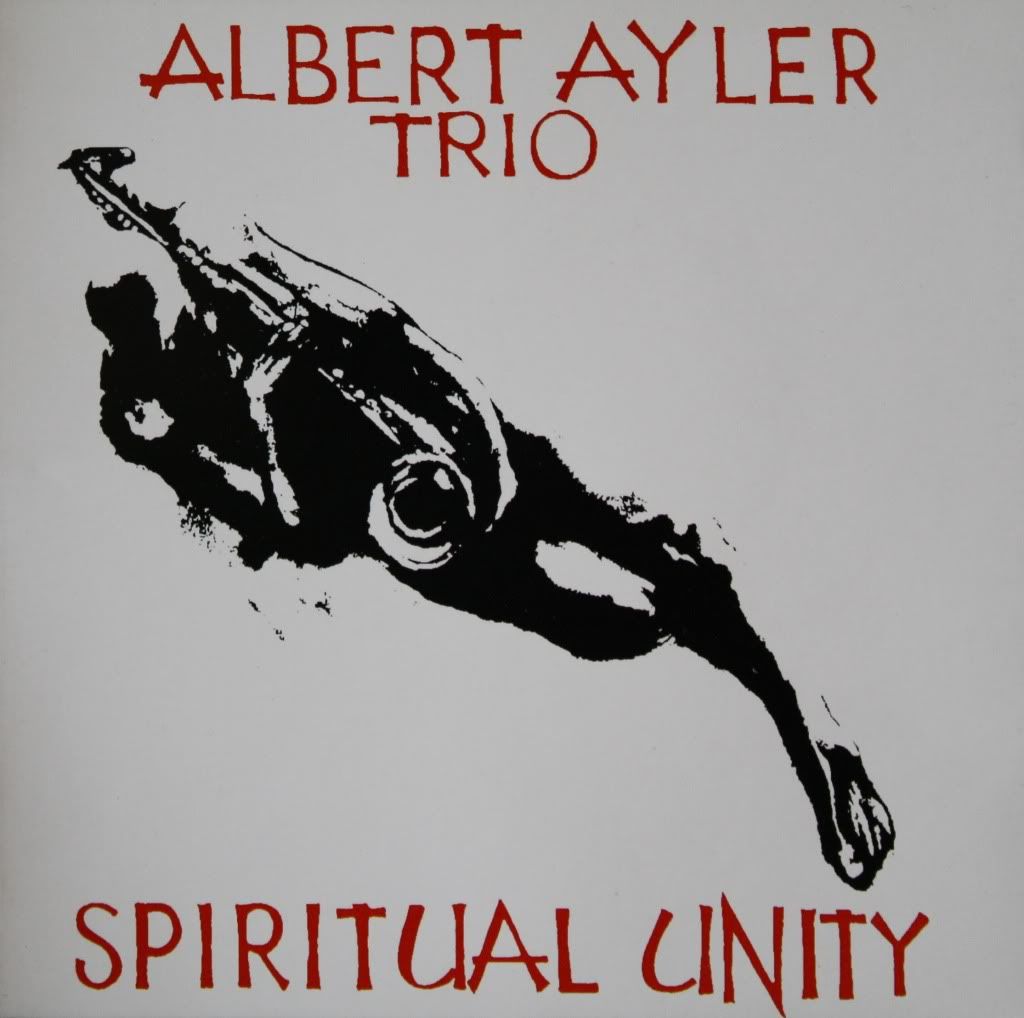

Albert Ayler - Spiritual Unity

Although I've mentioned free jazz a few times, I still haven't ever actually defined it or reviewed a full-on free jazz release. Although free jazz is a widely-accepted subdivision of the jazz genre, it came about gradually over a couple of decades (mostly the 1950's and 60's) and through the work of a number of pioneers, so it can be difficult to pin down exactly what its characteristics are. There is, for instance, a big difference between Ornette Coleman's unrestrained soloing over a relatively orthodox rhythm section in The Shape of Jazz to Come and some of the 20+ minute raging noisefests in Sun Ra's more audacious outings. The unifying principle behind most music labeled "free jazz," though, is the elimination of some of the more traditional restrictions of the jazz idiom--be they adhering to chord changes when soloing, playing the instrument in a traditional way, including a repeating melody in the song, ensemble members playing in the same key (or even the same tempo), or ensemble members paying attention to what the others are doing. It would also seem that free jazz places utmost importance on emotional expression--famous players have sought to avoid limitations in order to more authentically communicate their emotions through improvisation. There will always be critics who argue that no jazz is actually "free," pointing out that there's always some structure, repetition, or limit to how the music will sound, but I think this observation misses the point--few free jazz players have ever claimed complete freedom; rather, the idea is to become freer from the traditional structures of jazz. To this end, something that's interested me is the difference between free improvisation, a few examples of which I've already reviewed, and free jazz. It's usually pretty easy to identify free jazz from free improvisation or atonal modern classical music, as the instrumentation is usually traditional, and the style of playing seems almost always to obviously fall within the jazz idiom (a saxophonist's phrasing, for example) no matter how noisy or atonal it is. Free improvisation, on the other hand, often seems hell-bent on avoiding connections with any established musical idioms and more in combining elemental sound with the energy and unpredictability of improvisation. While I'm neither a jazz musician nor particularly knowledgeable on the subject, I've recently gotten to a place where I feel like I'm starting to appreciate the tenets of jazz (especially of the free variety) and can enjoy and talk about it on specific aesthetic grounds.

Albert Ayler's 1965 album Spiritual Unity seems to me to be a great introduction to free jazz as it bridges the gap between early free jazz efforts and the much more ethereal works to come. Ayler is widely regarded as one of the greatest free jazz saxophonists for his emphasis on timbre and characteristic vibrato-heavy style. The album is book ended by two different versions of a tune called "Ghosts." The first variation beautifully illustrates Ayler's stance in the free jazz movement--the piece opens with Ayler belting a winding gospel-influenced melody before gradually disassembling it over the course of the next five minutes only to recapitulate the original theme at the end. It's thrilling to listen as Ayler inverts intervals between the notes, perverting what was originally an extremely recognizable melody into an at times hilarious and at other times furiously energetic caricature. No matter how wild his trills and runs get, though, they still fit within the rhythmic footprint of the original theme. The drums and bass are barely on the map, too, wildly filling the space with sound and energy, which seems to suffice in place of an actual beat.

"The Wizard" continues to showcase Ayler's playing, beginning on an even shorter melodic motif before devolving into some of his rawest playing on the album--his harmonics and overblowing sound so amazing that it's easy to understand why some of the fathers of the movement believed texture alone could replace melody and harmony as the centerpiece of a solo. "Spirits" brings the tempo down, showcasing the rhythm section with a little more space and room for the bass and drums to play off of each other, while Ayler's tremulous vibrato communicates a wailing sort of mourning sound reminiscent of a New Orleans jazz funeral. The relatively short album closes with a second variation of "Ghosts" in which Ayler stretches beyond even the theme's rhythmic form, running all over the map during his solo and returning for more soloing after the bass and drum break before returning to the theme. Spiritual Unity unifies free soloing with highly unstructured rhythm section playing to delve pretty deeply into free jazz territory, but its utilization of recognizable themes and loose but undeniable song structures make it considerably more accessible than some free jazz outings. My only gripe is with the drummer, who spends too much time on the ride for my tastes, but I've got nothing bad to say about Ayler's stunning chops and energy.

Tuesday, June 21, 2011

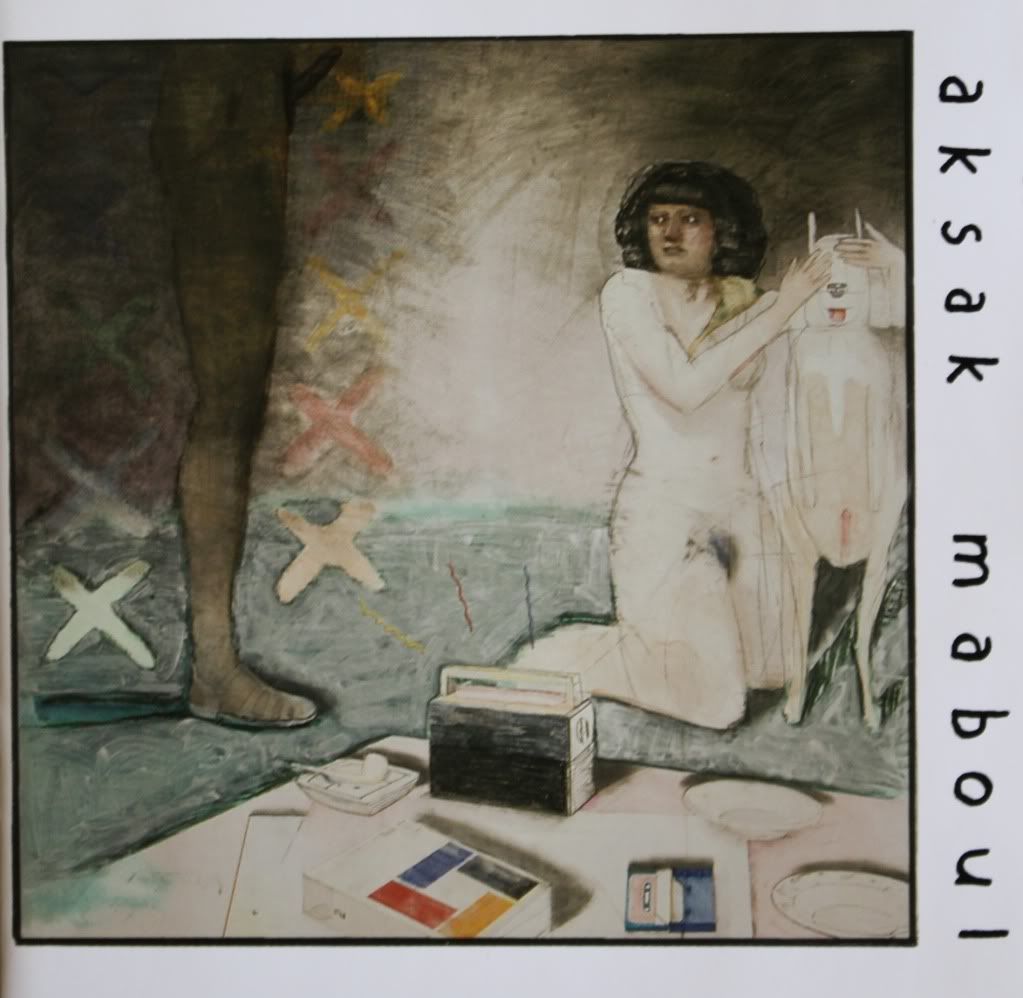

Aksak Maboul - Un Peu de l'Âme des Bandits

After a week that saw reviews for Brazilian pop, 60's folk and French pop, I feel it's time to travel back out into the...beyond. There's so much to say about this album, Belgian group Aksak Maboul, and RIO (Rock In Opposition) that I almost don't know where to start--let's begin with RIO. Rock In Opposition, though it's sometimes loosely used as a genre tag, was originally actually a festival organized by British group Henry Cow (with especial effort on the part of drummer Chris Cutler) in order to promote avant-garde rock groups selected by Cutler (eight in total) that were receiving little to no support from commercially-minded record companies. Though the movement was short-lived, it garnered a fair amount of press for the groups and, more importantly, facilitated the release of some of the most challenging progressive music produced throughout the 1970's and beyond. Since the loose movement became inactive in the 1980's, you're more likely to hear RIO referred to as a music genre used to describe either music that members of the original RIO groups have made, or music that is similar to, for example, Henry Cow's--dense, avant-garde, forward-looking, often with healthy doses of modern classical and jazz influences, though I personally don't find the tag to be the most helpful.

Belgian group Aksak Maboul was part of the second group of artists invited to RIO and was primarily the project of Marc Hollander (previously of CoS and founder of record label Crammed Discs). Aksak Maboul's 1977 debut was much more of a solo effort, with Hollander playing most of the instruments (a lot of keyboards, wind instruments and drum machines)--it's a playful, eclectic and enjoyable outing, but not today's album! In 1980, Hollander was joined by Henry Cow alumni Fred Frith and Chris Cutler and a few lesser-known European musicians for this, "their" second and final album. Though Aksak Maboul wasn't an original RIO group, I picked this album to introduce RIO because it's one of the most consistent, representative, and simply best RIO has to offer.

You know (or at least hope) from the ridiculous cover (depicting no fewer than two erections) that this album is going to be a crazy trip, and it certainly doesn't disappoint. Personally, I find this album extremely satisfying because of the experimentation--most all of the songs are based on at least one describable experiment, and the results are not only challenging, they're often quite listenable. A great example is the opener, "A Modern Lesson" (please, oh please, watch the video), which manages to deconstruct a classic blues riff with dissonance, drum machines, and wacked-out female vocals in under 6 seconds. As the track progresses, the wind instruments enter (along with some pinball machine recordings) for an interlude, the main riff returns, then the bass and tempo increase and Hollander's electronic keys and Frith's detuned guitars amp up the energy for a driving finale that sees an incredibly complex wind/key/string arrangement brimming with head-spinning counterpoint and--what elevates this beyond similar attempts--a memorable melody. "Palmiers en Pots" radically switches gears with a tango supposedly composed of (get this) pieces of several popular tangos, cut up with scissors, rearranged, and performed in random order.

That Fred Frith was on an unstoppable roll in the early 1980's, I'll never deny--his fingerprints (as musician, composer and producer) are all over this album, and in some ways it's better than its Frith solo contemporaries as his ideas (some heard already heard on other albums) are supplemented and developed by other musicians. Though the resulting disc doesn't exude quite as much of Hollander's personality as the Aksak Maboul debut, its diversity is one of its greatest assets--"Geistige Nacht" features a frantic sax-led melody with some great free jazz soloing in which the sax and eventually Frith's guitar trade squawks, and "I Viaggi Formano La Gioventu" features a snaking Middle-Eastern melody doubled on wordless vocal, violin that's strongly reminiscent of Frith's other 80's work, though that handclap track buried in the mix toward the end of the song shows up again on Cheap At Half the Price's "Absent Friends." "Inoculating Rabies" is probably the second best experiment on the disc, blending a balls-out punk riff driven by Frith's and Cutler's unfettered noise with the addition of a delicate woodwind arrangement. It's probably the best (if not only) progressive commentary on and appropriation of the burgeoning punk movement I've heard so far, which, by 1980, had all but swallowed what little market experimental progressive music like Aksak Maboul might have cornered. It's pretty ironic how loud Frith, bass and Cutler get considering how "obsolete" punk supposedly made their musical contributions.

The 23-minute-long "Cinema" rounds out the album with long-form composition interspersed with free improvisation (there's a lengthy and wicked cello solo as well as a pretty epic Fred Frith guitar solo), recording collage, a recurring sinister-sounding theme, some really heavy jamming from the full group (Cutler's drumming here is the liveliest I've heard since Henry Cow's last album, and recently, too). The melodies and ideas aren't quite as immediate as they are on the shorter songs, but the added space allows the group to accomplish some things that it couldn't in five minutes, and it gives us more to uncover on later listens. Pieces like this often seem to divide the camp of potentially interested listeners--take longer than five or six minutes and some people will complain about having their time wasted. If there are enough different ideas being developed, though, I don't mind it taking a while--as much as I'm leaning toward shorter songs packed with briefly-stated ideas these days, I can appreciate a piece that actually allows listeners to engage with and unravel the ideas being presented during the piece, rather than after numerous plays. While Hollander's personality is somewhat obscured by the thickness of the production and arrangements, it's perceptible on repeated listens, especially if you've heard his earlier works. I really enjoy his mechanical-sounding drum machines and keyboard lines, not to mention his contributions to the horn sections. Let's hear it for RIO, and this week let's keep going down the rabbit hole.

Available here on CD

Monday, June 20, 2011

Word Pillow Quietly Smother

` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` `

Comically I sitstanding before you

falling over myself

to describe fumbling profundities

nestled in between

just a pinch

of carefully selected words

What could I possibly use to describe them?

How about more words?

Only this time it'll be a duffel bag's worth

doled out in sloppy handfuls

so it's more like a stuffed word pillow

used to quietly smother the topic in its sleep

Allow me to mock a litany of useless things

while at the same time praising uselessness

Reassembling other people's ideas

behind a gauze of cheap pictures

Pretending self-seriousness and mockery

are somehow mutually exclusive

and in some way compensate for each other

Before reiterating one more time

my distaste for repetition

Patiently wait when I demand space

to carve a greedy slice of our hours for myself

in devotion to only the most unmarketable of pursuits

only to pass the time pursuing

only the most common of habits

Take notes as I distance myself

from the behavior of others

based on the proximity of our resemblance

Exclaiming that

What's to be done is that which has not yet been done

only to quickly retreat from the challenge

equivocating that these days

such things are a matter of degree

when I know full well I can't see that far

What, speaking?

I wasn't saying anything

` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` `

` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` `

` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` `

Whereas some of my other recent poems are composed of brilliant wordplay and jaw-droppingly profound ideas, this one was created pure self-loathing, sarcasm and disgust with my own hypocrisy. Enjoy!

Sunday, June 19, 2011

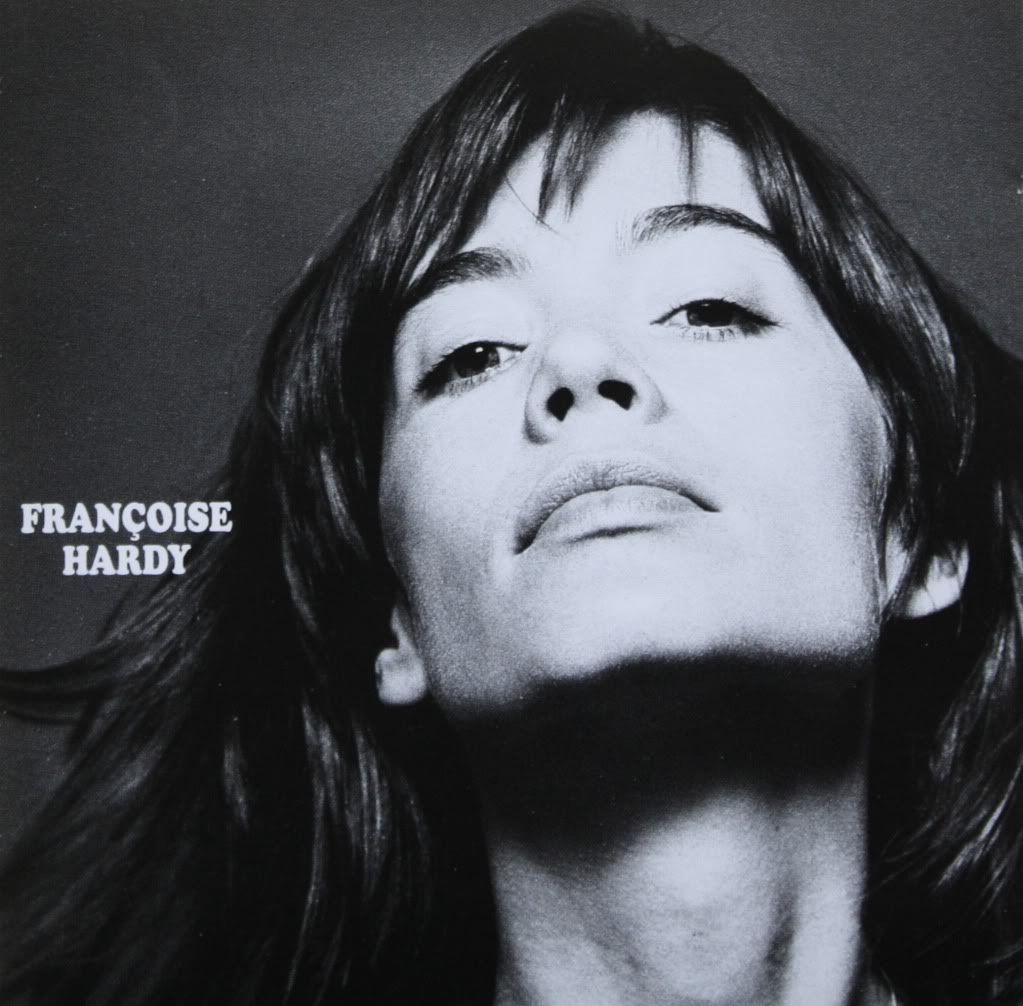

Françoise Hardy - La Question

After nine years and over 15 releases in the teen idol "Yé-yé" French pop style that first garnered her fame with 1962's hit Tous les garçons et les filles, Françoise Hardy decided to change gears. While some critics paint the stylistic shift that happened with La Question as some sort of radical change for Hardy, in reality it's less of an audacious move away from pop music and more of a subtle shift within pop to a more mysterious, atmospheric, and jazzy sound. Rather than the catchy but generic bubblegum pop sound of her early records where the limits of her vocal technique were often made obvious by the material, the soft dynamics and spacious mystery of this album's songs places more of an emphasis on the singer's personality while simultaneously cultivating a palpable mood. Hardy sings in a breathier, whispery style, only occasionally lifting her voice into the upper register--the contrast only makes the music more dramatic, and the feel more, well, like that look she's got on the cover.

Instrumentally, the album relies on the nylon-stringed acoustic guitar of co-writer and producer Tuca (a fairly obscure Brazillian performer), acoustic and electric bass, subtle percussion and occasional orchestrations. The swelling "Oui je dis adieu" gracefully bounces back and forth between the strings and guitar in simple yet effective counterpoint, while "Chanson d'O" showcases Hardy's seductively breathy vocals. An almost David Axelrod-esque tension drives the dark, cello-suffused opener, "Viens," and returns again on the disquieting opening of "Le Martien," though Tuca's bossa guitar riff eventually softens the ambiance. The only track that really breaks the dusky atmosphere is the sing-songy "Bati Mon Nid," with its "la-la-la" chorus where a male singer joins Hardy on vocals.

While hardly left-field, La Question is totally a high-water mark in Hardy's discography and one that holds up really well in spite of its age. The record's sultry atmosphere can't be beat when you're in the mood, but it also holds up pretty well if you're actually paying attention.

Get it here on CD

Saturday, June 18, 2011

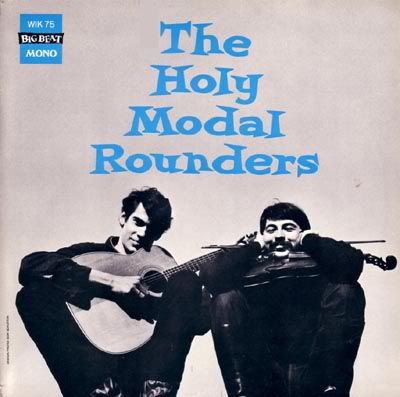

The Holy Modal Rounders - The Holy Modal Rounders

In my opinion, the word "folk" is egregiously overused. From Mumford and Sons to America to Iron and Wine, the genre "folk music" is broadly applied to groups that emphasize acoustic instrumentation, don't have a heavy rock sound, and rarely have anything to do with the folk tradition. That is, the playing of actual folk music; traditional songs that have been passed down for generations and continually altered by performers insofar as the music becomes a living tradition that's continually changing and evolving. While I agree that there can be a difficulty in accurately describing the type of music that the aforementioned artists make, it's really not folk in any technical sense, and so describing it only dilutes the potency and clarity of a great word and concept--"folk" can be used to describe all manner of participation in the folk tradition from the likes of Ralph Vaughan Williams' and Béla Bartók's collection and assimilation of folk melodies into their classical works, to Harry Smith's anthology of various real people playing their renditions of American folk songs, to Bob Dylan's wholesale "theft" (a cornerstone of the folk tradition) and reassembly of everything from folk melodies, folk lyrics, literary and historical figures, and pop culture, which just might stand as the single greatest modern expression of the living folk idiom seen in the 20th century. Anyway, the totality of the folk tradition is both messy and diffuse and I have no intention to stridently decide who is and isn't a folk artist (part of the allure is folk's all-encompassing, diverse nature), but one of the groups and albums that most immediately comes to mind when I think of the precise definition of "folk" is The Holy Modal Rounders and their 1964 debut.

Though it later swelled in its later-60's incarnations, the Rounders started as a duo--Steve Weber and Peter Stampfel (with whom I'm proud to say I'm facebook friends), who were highly active in the NYC folk revival of the early 60's and were also involved in The Fugs. That association alone might give you a pretty good clue as to the Rounders' approach to folk music--irreverance abounds as Weber (guitar) and Stampfel (fiddle, banjo) trade vocals in ridiculous voices (Weber's got the sort of wheezy one and Stampfel's the nasaly one) across a selection of Rounders-arranged traditional folk tunes like the classic "The Cuckoo," "Same Old Man," "Give the Fiddler A Dram" and "Bound to Lose." As folk musicians are wont to do, the pair not only arrange the songs with a number of comic flourishes, they also mess around with some of the lines to make the songs their own. Although the arrangements are simple, they're subtle--Weber's guitar forms the framework for many of the songs, like "Blues in the Bottle," where he lays down the guitar foundation and Stampfel's fiddle periodically appears to lend its scratchy warmth to the melodic refrain--much more effective than if it were played for the song's entirety.

What really sets this album above the standard folk fare (especially the kind of contrived anachronistic old-timey stuff that a lot of today's folk revivalists are into) are the excellent handful of original songs peppered throughout the collection--the fantastic "Hesitation Blues," which just might feature the first recorded use of the word "psych-o-delic" (as the band says it) and some subtle harmony vocals. And then there's the hilarious nonsense and onomatopoeia of "Mr. Spaceman," and the druggy glory of "Euphoria" [Update 2/20/12: I'm told "Hesitation Blues" actually isn't an original tune but an update of a song recorded earlier by Crying Sam Collins, thanks Mel!] The duo manage to adapt their original tunes to their folk style with traditional-sounding melodies and the most important ingredient of folk music--collective fun. If only they'd broken beyond cult status, perhaps more of today's folkies would be playing their own versions of Rounders' originals. As it stands, this album is a great time and a shot in the arm for what's sometimes a pretty musty genre.

You can get it on CD here , along with their enjoyable but not quite as sparkling second album.

, along with their enjoyable but not quite as sparkling second album.

Though it later swelled in its later-60's incarnations, the Rounders started as a duo--Steve Weber and Peter Stampfel (with whom I'm proud to say I'm facebook friends), who were highly active in the NYC folk revival of the early 60's and were also involved in The Fugs. That association alone might give you a pretty good clue as to the Rounders' approach to folk music--irreverance abounds as Weber (guitar) and Stampfel (fiddle, banjo) trade vocals in ridiculous voices (Weber's got the sort of wheezy one and Stampfel's the nasaly one) across a selection of Rounders-arranged traditional folk tunes like the classic "The Cuckoo," "Same Old Man," "Give the Fiddler A Dram" and "Bound to Lose." As folk musicians are wont to do, the pair not only arrange the songs with a number of comic flourishes, they also mess around with some of the lines to make the songs their own. Although the arrangements are simple, they're subtle--Weber's guitar forms the framework for many of the songs, like "Blues in the Bottle," where he lays down the guitar foundation and Stampfel's fiddle periodically appears to lend its scratchy warmth to the melodic refrain--much more effective than if it were played for the song's entirety.

What really sets this album above the standard folk fare (especially the kind of contrived anachronistic old-timey stuff that a lot of today's folk revivalists are into) are the excellent handful of original songs peppered throughout the collection--the fantastic "Hesitation Blues," which just might feature the first recorded use of the word "psych-o-delic" (as the band says it) and some subtle harmony vocals. And then there's the hilarious nonsense and onomatopoeia of "Mr. Spaceman," and the druggy glory of "Euphoria" [Update 2/20/12: I'm told "Hesitation Blues" actually isn't an original tune but an update of a song recorded earlier by Crying Sam Collins, thanks Mel!] The duo manage to adapt their original tunes to their folk style with traditional-sounding melodies and the most important ingredient of folk music--collective fun. If only they'd broken beyond cult status, perhaps more of today's folkies would be playing their own versions of Rounders' originals. As it stands, this album is a great time and a shot in the arm for what's sometimes a pretty musty genre.

You can get it on CD here

Thursday, June 16, 2011

Jorge Ben - A Tábua De Esmeralda

I'm excited today to delve into some areas I haven't yet written about on this blog. Jorge Ben is one of the most popular and enduring Brazilian artists of the past 50 years, so featuring one of his best albums is a good way to start discussing Brazilian popular music of the 60's and 70's.

1974's A Tábua De Esmeralda is widely viewed as a high-water mark for both Ben and the MPB (Música Popular Brasileira) genre as a whole. While MPB is a rather broad term that's used to describe almost any popular usic coming out of Brazil in the 60's and 70's, its lack of specificity is often reflected in the blinding eclecticism of the artists it's used to describe. Jorge Ben is a perfect example--his songs' rhythms and distinctive nylon-string guitar style gives the music away as samba, but there's so much more to it than that! The album-starting "Os alquimistas estão chegando os alquimistas" (which is about alchemists, of all things) fits the samba mold with Ben's upbeat strumming, a bouncy beat, hand percussion and a small chorus backing up the Ben's smooth but expressive vocals. And yet, the track opens with some Portuguese mumbling and the track is adorned with sweeping strings and flutes, which build like a storm in the background toward the track's end. Similarly, the second track, "O homem da gravata florida" is deceptively straightforward in its simplicity, but Ben's vocals are increasingly reverbed and delayed to the point that things get a little...well, trippy. This mood reaches a peak on one of my favorite cuts, "Errare humanum est," which opens with an innocent "la la" chorus melody but progresses into a moody, layered atmosphere where pumping cellos duel with the drummer's pounding toms and Ben's plaintive vocals effortlessly dance between his reedy mid register and smooth falsetto and cascade into an infinity of cavernous echoes. How he manages to achieve a mood that's simultaneously joyful, dark, mellow and energetic is beyond me.

While the production flourishes do add a psychedelic flavor to the songs, this is a long way from the sometimes-manic style to be found in late-60's Tropicália, a much more political and edgy subset of MPB spearheaded by artists like Caetano Veloso and Gilberto Gil--there's no sanity-threatening sonic collages or bursts of noise. Instead, Ben's songs--brimming with melody--and his personality as a performer carry the show. While in some ways the strings and echo make the album, it's easy to imagine these songs standing on their own in a live setting with a smaller, mostly acoustic ensemble. While I freely admit that Portuguese is impenetrable to my ears, this album is close to the top of my list of foreign language records where it doesn't matter if you don't understand the words--of course, it helps that a lot of the refrains are wordless. I can only imagine how knowing the words would enhance this already sumptuous listening experience. Of course, there is one song sung in English--"Brother"--which sort of breaks the spell with its Jesus message, but it's one of the catchiest cuts on the album, so it's hard to begrudge it for its mundane religious message alone.

Of the Jorge Ben albums I own, this one regularly dukes it out for top spot with his also-brilliant Africa Brasil from 1976. Unfortunately this album (along with much of the tragically poorly-curated Tropicalia and MPB legacy) is out of print, but it's available used and in high quality MP3 for a reasonable price here.

Tuesday, June 14, 2011

Gone Man Bleat

` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` `

Just back thereYou--bespoketacled

Planes swimming across oceans of

Truth is the flast flame that's gone all too qulickly

You granted us a shriek peek into the either

(against our baddered judgmental expectorations)

Hollering rowder

before you blurred yourself out of fuck-us

one weak after naut floating above the space shit

your only way back down

Then you dinged back in just in time

to make use of the last of the

un-un-un-unquoinium

before we even triggered out how to synthefy it!

The things that so hrashly know us down

over

under

do they flaunt us in kept gossipy wings

only to disreappear to take the piss out of us

spoiling the mictury

no longer supplising the grizzly necessiprocities?

The flings we chuck up

Is their contritioning enough to

bent-dumbbell-tricep-row us

up

out of this ditch crack cave

we've begotten ourselves unto?

Should youn't be fiftied a don't-worry-about-it

we saw we our supposed deserved fine ale?

` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` `

` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` `

` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` `

This elegy for Don Van Vliet considers the man's accomplishments and reflects my frustration that

Monday, June 6, 2011

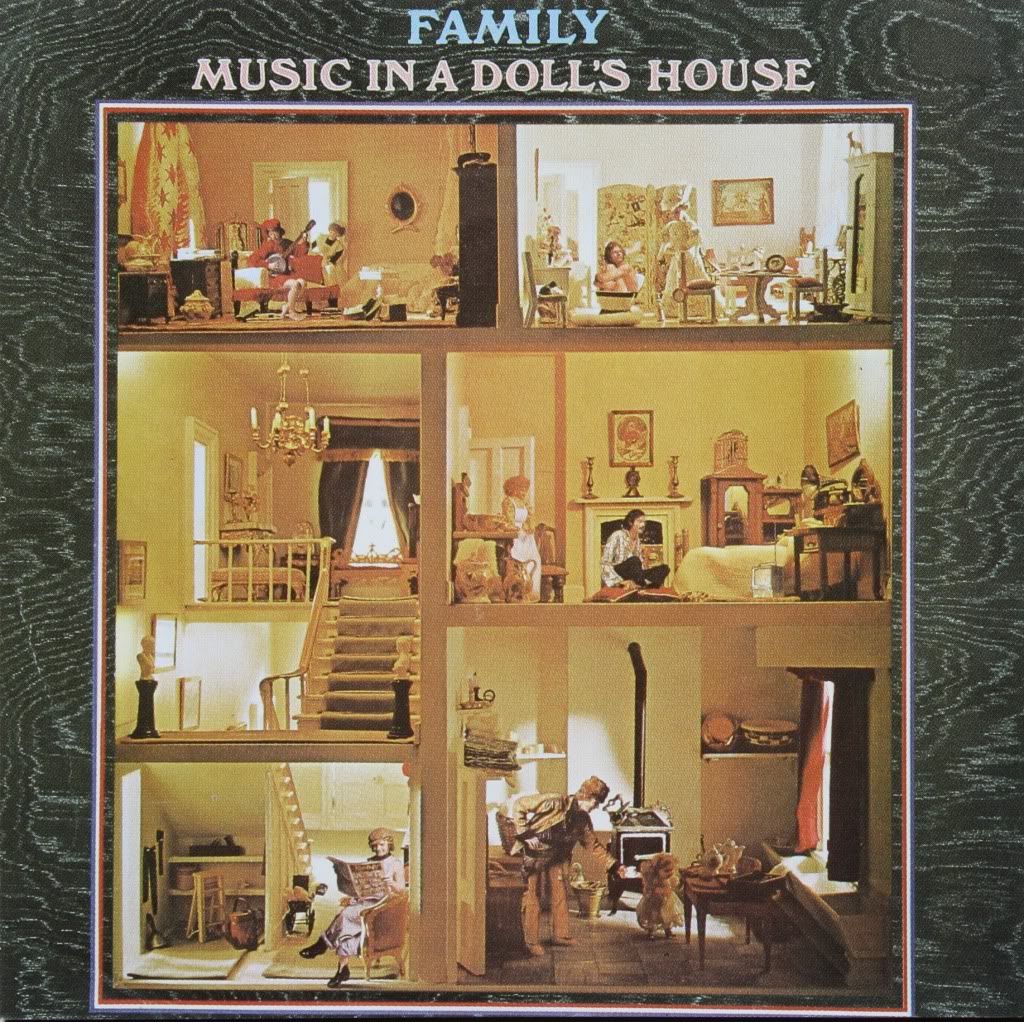

Family - Music In A Doll's House

When Family's debut hit the shelves in 1968, it must have sounded like positively nothing else--retrospectively, it's hard to really tie them to any other specific movements or bands, with their layered sound employing familiar rock instrumentation as well as saxophone, brass horns, harmonica, strings and mellotron. The closest I can come is perhaps Traffic, but Traffic's sound is so married with pop, soul and blues that it can't hold a candle to Family in terms of sheer weirdness.

Of course, a good deal of the band's strangeness is owed to lead singer Roger Chapman's powerfully thick, tremulous vocals. As far as I know, he's got no stylistic equal in the history of rock music, and his brio certainly adds a unifying, distinctive character to what is an extremely eclectic collection of songs. The demonic wailing that kicks off "The Chase" should be evidence enough that you're in for a strange trip, and as the track gallops through baroque textures and detuned horns, you know you're not coming back for a good 40 minutes. From the opener out, it's an unpredictable ride through shimmering ballads ("Mellowing Gray," "The Breeze"), trippy pop ("Never Like This," "Winter," "3 X Time"), blues broken up by progressive interludes ("Old Songs For New Songs," "Hey Mr. Policeman"), and dark rock of a definite other quality ("Me My Friend," "Voyage," "Peace of Mind," "See Through Windows"), to which I find myself gravitating the most--the latter combines an addictive psychedelic guitar riff with perfect timing lyrically--"See through...windows...Look...at things."

For what's ostensibly a rock album, it takes quite a few listens to fully apprehend all that transpires within--the songs are short, mostly under three minutes, and there are even shorter interludes in between that play with a handful of the songs' melodies and briefly present them in different settings. With all of the eclecticism and wealth of ideas presented here, I'm pretty much obligated to artistically appreciate this album, which I do--I especially admire the band's ability to pack in the ideas and different textures within the space of short songs, often stating ideas without overly repeating them (nothing's worse than heavy-handed repetition). Still, a couple things hold this album back from the next level for me. First, in spite of the diversity in songwriting and instrumentation, I often find myself hoping for something harder--Chapman's voice is probably the hardest thing on the album, and a lot of the songs feel weirdly lush without carrying as much force as they feel like they should. Additionally, there's something unquantifiable about some of the melodies and ideas that indicates they don't always have the natural flair for distinction and memorability that sets good bands apart from great ones. This is probably the most artistically troubling thing about this album for me personally--that you can put the effort in to really cram an album with surprises every few seconds and it still isn't "great." Who knows--perhaps I just haven't listened enough times to assimilate all the data. After all, that is one of the best things about music that's dense with ideas.

Ultimately, Music In A Doll's House sits in that strange gap between late-60's psychedelia and 70's progressive rock. Strangely, I like it a lot more than most proto-progressive albums I've heard, as there is some genuinely feverish experimentation happening from a songwriting perspective, and despite the eclecticism the band has a certain focus. Unfortunately, the further Family went, the less focused they became--even their second album featured the drastic change of handing Chapman (by far their most distinctive element) only half of the lead vocals. Many a good band has been mired in mediocrity thanks to an overemphasis on democracy--sometimes, there's something to be said for numerous players supporting the vision of one or two in the name of better results.

Get it here on CD

Saturday, June 4, 2011

Constructing a Shell

` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` `

I'm constructing a shellCollecting necessities, I'll form the walls--make them thick

When I have enough to last a while, I'll collect some more!

A soft quilt for my shelter

And how about when I have enough that I'll never run out?

It's possible to gather useful things before you need them

before you even have them

This is what's called

"invisible stones"

That's what I'll use to shape the tower--invisible stones

I'll wave to you from inside the tower when you pass by

I'm working something out inside!

When the walls are high, I might decide to dress the place up a bit

at which time I'll probably start acquiring what's known as

"see-through paintings"

I can dodge recurring fears and avoid other types of trouble

using see-through paintings

--to a point

Eventually, I'll vacate

The tower, lying on its side, might not look like much at all

But people will definitely want some of the see-through paintings

And the invisible stones will be useful to those

who can get their hands on what's left of them

As for the rest

some of it might come in handy to others with similarly-sized

desires

but most of it will be useless, unwanted

cold without the heat of my need

And yet, it will have to go somewhere

Both useful and useless tossed in a salad of use

less

ness

Still sitting, staying safe

secure

While I sit somewhere, somehow

else

` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` `

` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` `

` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` `

More conventional and expository (if still pretty surreal) than the last poem I posted, save a bit of alliteration toward the end. This poem is sort of an extended metaphor about our relationship with different types of material things and the extremely surreal power attributed to completely intangible concepts like money, which, regardless of the amount, is only a representation of the ability to get more things. How many shells can a hermit crab use at any given time?

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)