Hiding from Heaven

Elbows gasping, nails bleeding—following electricity (whatever THAT is)

I fought my way out of a box to find myself in a bigger box

Then it hit me—it’s not about boxes!

They’re always collapsing—you’re always in the (W)ay

If you think you’re outside the box, then you forgot

The hardest rocks are the ones rattling round inside our heads--Dead!

I found you no longer breathing from your heels

But from your throat!

Each radical breath you take is speeding you to

The shallow grave your lungs are digging for you

It will be filled by a frail form that failed to feel the flailing madness

In the old days they called it ‘hiding from heaven’—back in the day

These days they call it “faith”

Ears sputtering, spine coughing—chased down by stars (whatever THEY are)

I sucked to empty self-fulfilling prophecies, filling my saintly virtue

Til the whole of my being leaked excess in puddles on the floor

What’s more—I awoke to find my “I”ness gone

In its place, a view through the eye of the storm

Can I trouble you to stop a sec, explain why death’s so bad

When everything that ever lived on earth is dead except for this now

Huh? Huh? Don’t make me laugh!

You reek of a living way of thinking, stinking of “human first”—“life as good”

You’re clawing forward as you fall back instead of graciously giving yourself to

A deep grave, gallantly going on with the great game, gulping gutfuls of ground

Grasp the gatekeeper’s grip when you gasp in a new way

In the old days they called it “hiding from heaven”—back in the day

These days they call it “salvation”

` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` ` `

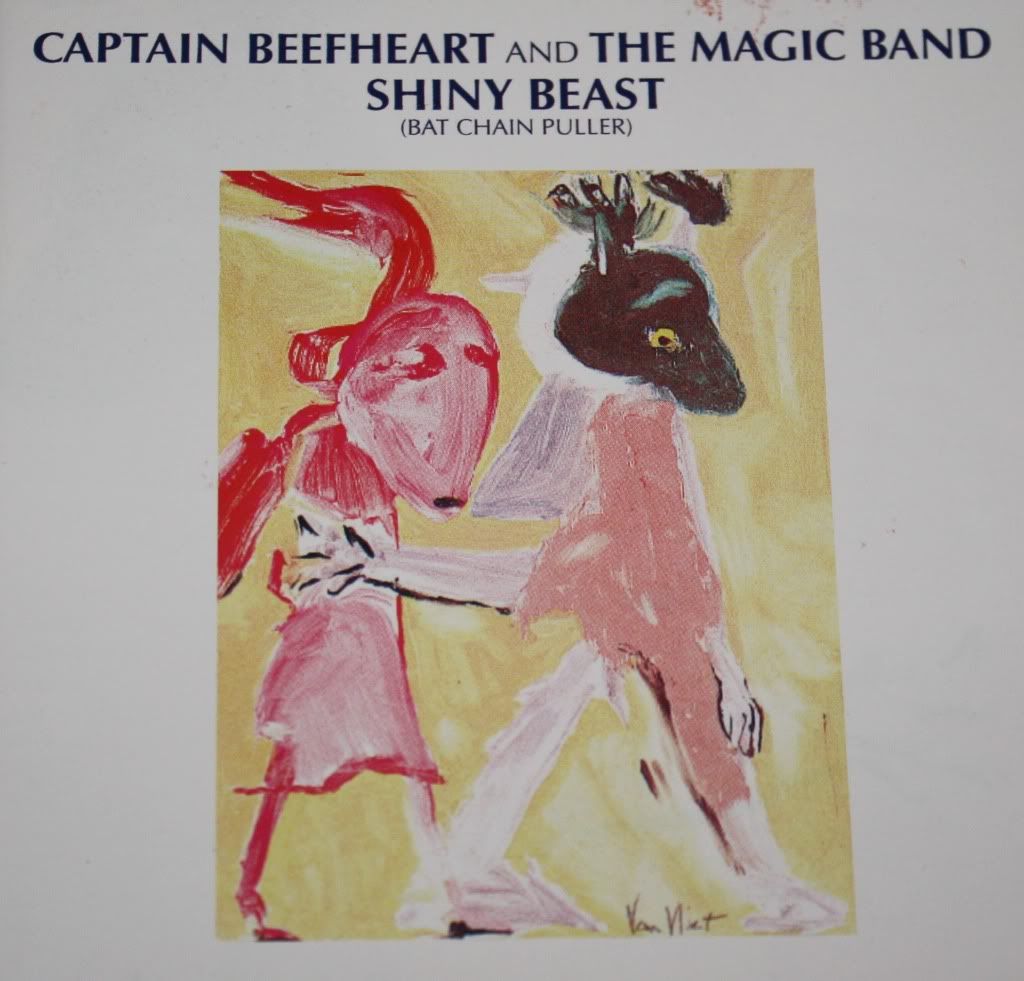

Before I launch into what’s likely to be another tiresome rant, let me just comment on that very subject. This is the reason I love and MUST practice music and songwriting. You can discuss these things with prose, but you’ll never achieve the thrill of understanding the same (or many more) ideas from only five, well-chosen and aesthetically appealing words. You can write poems about these ideas, but you can never feel the same sublime, soaring feeling or crushing weight without the addition of music and at least one singing human voice. There’s something irreplaceable in that combination, and the coalescence of popular music’s conciseness and accessibility with high art’s depth, audacity and range of emotion is dizzyingly intoxicating—a vein that I can see myself mining for the rest of my days. So, I’ll try to explain myself in these entries, but only for those interested in a different perspective on the sounds than they’ve already provided themselves, and also, personally, to help me understand what I actually think myself.

Out of these 11 songs, “Hiding from Heaven” is unequivocally my baby…a “Rosemary’s” baby of sorts, but no less loved for it. Ever since it began its 2+ year gestation period on the back patio of the farm as an enormous, serpentine, wonky poem, this song has constantly harassed my thoughts. It took two years before I had fit the entire asymmetrical shape of the poem to music, and when it came to recording, “Hiding from Heaven” was the first song I started in November and one of the last ones finished in early April (most of the songs took 1-2 hours to mix, this one took over 4). A lot of thoughts were expended on how best to translate the booming din I’d been hearing in my head into a thing of dark, terrible majesty (insert “yeah, Elliot, it really is TERRIBLE” joke here) and you can rest assured I started feeling sympathetic pangs of the song’s professed madness in the process.

Musically, the song is a culmination of a large number of influences, tempered with a sense of my own personality. Despite its length, the song moves quickly and often abruptly between different musical sections—from the dissonant and odd-metered intro to the spacious first vocal section, the proggy breakdown, etc. I’ve tried my hardest to populate this song with guitar riffs and leads that other players will appreciate, but also that don’t tread the same ground too many times, playing with the song’s themes, dissonance, listener expectations and musical styles. A lot of these parts didn’t seem humanly possible when I started attempting takes, so hopefully that’s a good sign…most importantly, though, they strive to support the song’s overarching ideas. This principle has been crucial for all of these songs, but “Hiding from Heaven” required even more reaching on my part to bring the ideas to fruition—I used (but by no means invented) a few different techniques to get uncommon sounds out of the guitar. The eerie sustained notes at 1:45 are produced by a rubbing/tapping a steel slide on the strings; the single notes with the high-pitched texture around 3:10 come from scraping the pick perpendicularly against the strings windings instead of plucking. Finally, I couldn’t have realized my ideals for this song if my voice hadn’t gotten better. The theatrics you already heard in “No More” are turned up a notch in so many ways and the emotional brunt of the poem required a number of different singing styles and moments of strangeness and wildness to illustrate its intensity. I mention all of this out of a sense of accomplishment, but also to give you an idea of just how obsessively hard I worked to make this song sound how it does.

Lyrically, this is a long and complicated song. It’s heavily influenced by the ideas of and uses a few images from the ancient Taoist text, the Chuang-Tzu to illustrate a feverishly personal mind journey. You know you’re in for a fun time when a song starts with sensory dissociation and disbelief in such “comprehensible” and “tangible” items as electricity and stars…teetering on the edge. The one thing I keep thinking of when rounding up my thoughts for this note is Thomas Paine’s revolutionary “Common Sense” pamphlet—“Hiding from Heaven” means ignoring common sense—the way things simply are—attempting to circumvent demonstrable reality in favor of a coddling lollipop philosophy that panders to our most selfish indulgences. In my opinion, the major religious traditions offered in the world’s marketplace today offer solutions to undeniable human needs that insult our progress as thinking beings. Despite everything our science, art and long historical record has shown us, the best we can come up with is still an anthropomorphized “god” who created everything and will reward us with an eternal “after”life that fulfills all of our creature wants and pacifies all of our living fears—that is, only if we follow the arbitrary system of morality in the book that He (never She) wrote! Please! First of all, our infinitesimal scientific knowledge about the vastness of the universe, physics and biology here on earth demonstrate that a human-centric vision of the universe is a laughable proposition—on top of that, an omnipotent god that looks like a human and any system that is so clearly tailored to compensate for and satisfy human-only desires can only be human creations. Secondly, the justification for this system can be distilled to just one element—fear: fear of not having enough to eat, fear of physical pain, fear of losing loved ones, and fear of the inexplicable experience of death. These fears are entirely reasonable aspects of the human condition, but I think that we, as thinking creatures, deserve a better response than the utter fantasy that is fed to us by the religious institutions who can’t see beyond their own experience of power. There are currently a lot of social and environmental threats to our human world, but we can’t fight them effectively if we don’t address the fundamental ways of thinking that spawn them.

In spite of the above, this song isn’t merely another attempt to tear down organized religion—all you need for that is a bit of common sense, and it’s been done eloquently and effectively many times in the past 200+ years, regardless of whether or not the masses have climbed on board. Rather, it’s an attempt to address the same base human dilemmas in a way that takes into account our current advances (which should be obvious enough to be taken for granted) and reaches beyond to the unknowable to postulate a meaning—a rational mystic’s rally call. Sure, it’s much more difficult than jumping through moral hoops for a pie in the sky, but it’s ultimately a lot more rewarding and realistic.

Achievement of this sort of reconciliation not only requires abandonment of the status quo, but also engagement of our mystical potential (see “Head in the Clouds,” which also cautions against over-rationalization)—it requires intuitive experience of the Tao—(a descriptor for) the ineffable, indescribable, incomprehensible, inhuman, infinite and chaotic way the universe operates and is. For me personally, this process was a turbulent one that included several points of despair. When it comes to conjuring visions of the holistic nature of the universe, there’s a fine line between despair and ecstasy—easing the attachment to the knee-jerk ego response and ultimately abandoning the arrogance of any sense of human importance in the universe eventually replaces fear and despair with serene calmness and even sublime ecstasy. It’s not the human that takes first place, but the awe-inspiring, all-inclusive storm of the universe, from which we’re kidding ourselves if we say we’re separate. Death of a living organism is just one of incalculable aspects of the universe, and seen in such a vast perspective isn’t very dramatic at all. As the only living creatures (we’re aware of) that have the ability to contemplate the void, death is less of a loss of our beloved senses to be feared, and more of a reunification with the one to be anticipated when the time comes—to me a concept much more empowering, exciting and “other” than an eternity of sensory fulfillment on a cloud. So, despite the song’s foreboding atmosphere, the message is ultimately a positive (if challenging) one. Oh, and just remember—these are all opinions.

There, I finally got some ideas across without explaining the song line by line! I am pretty satisfied with the aesthetics of this song, though, and if you’ll indulge my hubris I’ll mention a line that indicates the layered detail that went into the word choice for the whole poem: “I sucked to empty self-fulfilling prophecies, filling my saintly virtue/till the whole of my being leaked excess in puddles on the floor,” which can be variously taken to mean “I sucked” (in the parlance of our time), “I sucked/latched [on]to self-fulfilling prophecies that were empty,” and “I sucked self-fulfilling prophecies until they were empty.”

Not sure how much I like this professor Elliot…luckily tomorrow’s song doesn’t require his services in the least, and he won’t be coming back in this capacity any time soon.