Although I've mentioned free jazz a few times, I still haven't ever actually defined it or reviewed a full-on free jazz release. Although free jazz is a widely-accepted subdivision of the jazz genre, it came about gradually over a couple of decades (mostly the 1950's and 60's) and through the work of a number of pioneers, so it can be difficult to pin down exactly what its characteristics are. There is, for instance, a big difference between Ornette Coleman's unrestrained soloing over a relatively orthodox rhythm section in The Shape of Jazz to Come and some of the 20+ minute raging noisefests in Sun Ra's more audacious outings. The unifying principle behind most music labeled "free jazz," though, is the elimination of some of the more traditional restrictions of the jazz idiom--be they adhering to chord changes when soloing, playing the instrument in a traditional way, including a repeating melody in the song, ensemble members playing in the same key (or even the same tempo), or ensemble members paying attention to what the others are doing. It would also seem that free jazz places utmost importance on emotional expression--famous players have sought to avoid limitations in order to more authentically communicate their emotions through improvisation. There will always be critics who argue that no jazz is actually "free," pointing out that there's always some structure, repetition, or limit to how the music will sound, but I think this observation misses the point--few free jazz players have ever claimed complete freedom; rather, the idea is to become freer from the traditional structures of jazz. To this end, something that's interested me is the difference between free improvisation, a few examples of which I've already reviewed, and free jazz. It's usually pretty easy to identify free jazz from free improvisation or atonal modern classical music, as the instrumentation is usually traditional, and the style of playing seems almost always to obviously fall within the jazz idiom (a saxophonist's phrasing, for example) no matter how noisy or atonal it is. Free improvisation, on the other hand, often seems hell-bent on avoiding connections with any established musical idioms and more in combining elemental sound with the energy and unpredictability of improvisation. While I'm neither a jazz musician nor particularly knowledgeable on the subject, I've recently gotten to a place where I feel like I'm starting to appreciate the tenets of jazz (especially of the free variety) and can enjoy and talk about it on specific aesthetic grounds.

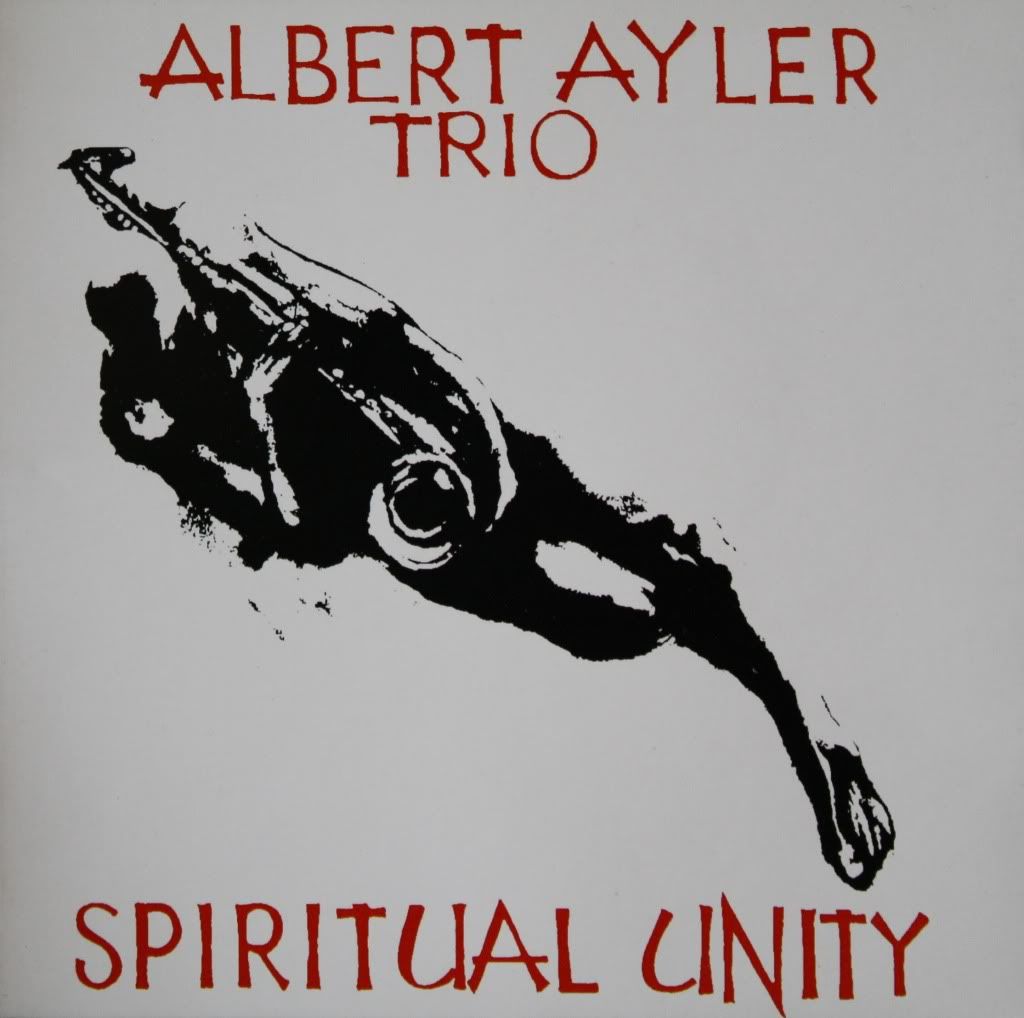

Albert Ayler's 1965 album Spiritual Unity seems to me to be a great introduction to free jazz as it bridges the gap between early free jazz efforts and the much more ethereal works to come. Ayler is widely regarded as one of the greatest free jazz saxophonists for his emphasis on timbre and characteristic vibrato-heavy style. The album is book ended by two different versions of a tune called "Ghosts." The first variation beautifully illustrates Ayler's stance in the free jazz movement--the piece opens with Ayler belting a winding gospel-influenced melody before gradually disassembling it over the course of the next five minutes only to recapitulate the original theme at the end. It's thrilling to listen as Ayler inverts intervals between the notes, perverting what was originally an extremely recognizable melody into an at times hilarious and at other times furiously energetic caricature. No matter how wild his trills and runs get, though, they still fit within the rhythmic footprint of the original theme. The drums and bass are barely on the map, too, wildly filling the space with sound and energy, which seems to suffice in place of an actual beat.

"The Wizard" continues to showcase Ayler's playing, beginning on an even shorter melodic motif before devolving into some of his rawest playing on the album--his harmonics and overblowing sound so amazing that it's easy to understand why some of the fathers of the movement believed texture alone could replace melody and harmony as the centerpiece of a solo. "Spirits" brings the tempo down, showcasing the rhythm section with a little more space and room for the bass and drums to play off of each other, while Ayler's tremulous vibrato communicates a wailing sort of mourning sound reminiscent of a New Orleans jazz funeral. The relatively short album closes with a second variation of "Ghosts" in which Ayler stretches beyond even the theme's rhythmic form, running all over the map during his solo and returning for more soloing after the bass and drum break before returning to the theme. Spiritual Unity unifies free soloing with highly unstructured rhythm section playing to delve pretty deeply into free jazz territory, but its utilization of recognizable themes and loose but undeniable song structures make it considerably more accessible than some free jazz outings. My only gripe is with the drummer, who spends too much time on the ride for my tastes, but I've got nothing bad to say about Ayler's stunning chops and energy.

No comments:

Post a Comment