Monday, July 18, 2011

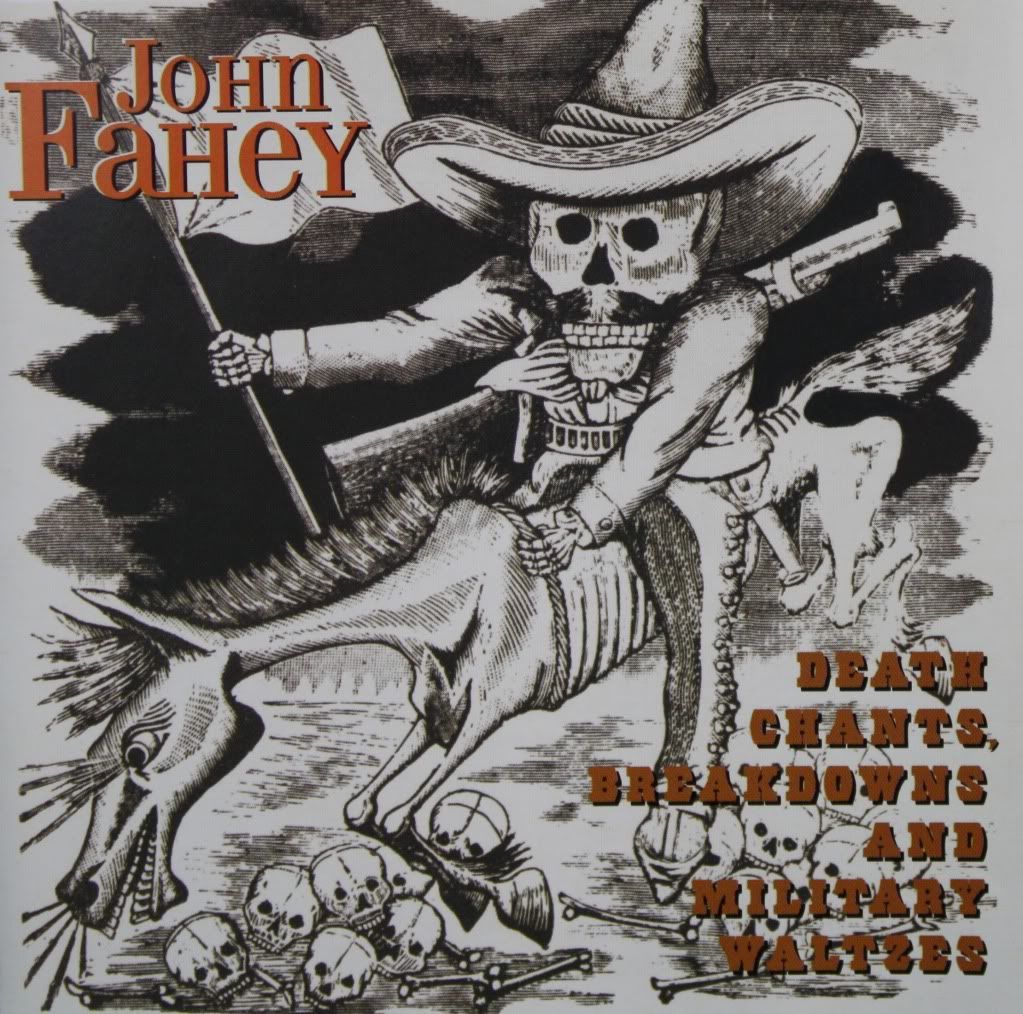

John Fahey - Death Chants, Breakdowns and Military Waltzes

In laying out markers for my musical landscape and contextualizing some of the other reviews I've written, I've been totally remiss in not yet mentioning John Fahey--sole creator of the solo steel string guitar genre, acoustic blues fanatic, composer and innovator--so I'll start with my first Fahey disc, and an enduring favorite from a man whose first 15 recorded years spanned an astonishing array of progression while still remaining anchored in the blues.

Death Chants, Breakdowns and Military Waltzes is John Fahey's second album, released on his own Takoma Records in 1963, four years after his unassuming but iconic debut. The intervening years allowed Fahey to significantly refine his technique (mostly open tunings, allowing for lots of octave Travis picking, arpeggiatos and some majestic slow strums with blues-cum-classical melodies played on the high strings) as well as his compositional style, which sees the song lengths stretching out and the compositions featuring more surprising changes and contrasting movements. Take "Stomping Tonight on the Pennsylvania/Alabama Border," which begins with a string-bending slow blues with a turnaround, mutates into a free, ascending arpeggio on the high strings, then again to a crushing minor blues dirge before revisiting each of its sections and closing on an arpeggio that crosses through dissonance to a dreamy major 7th concluding passage.

Like a lot of albums that have become long-term favorites of mine, part of what I love about this album is how it sounds--the recording quality isn't great, but since it's (mostly) just one instrument, everything's still audible and the music is laced with an antique atmosphere--and the room reverb is awesome. There are a few moments where the volume of Fahey's guitar threatens to distort the recording equipment (to its great) as on the slide glissando of "On the Beach of Waikiki," or where the distance of the guitar to the microphone lends a raucous feel, as on the energetic "Spanish Dance," and then on "John Henry Variations" when the instrument's slightly out-of-tune harmonic overtones warble with an unsettling but hypnotic pulse. If I call some of this album "psychedelic," it's these sort of extra-melodic elements that I'm talking about, like 3:15 into "America" where (through the use of tape editing, I assume) the guitar timbre suddenly changes from bassy fingerstyle to tinny high-neck strumming, or 1:06 into "When the Springtime Comes Again," when the key abruptly shifts from minor to major but the theme remains almost the same--there's something within those quavering intervals that lingers on the precipice of some forgotten memory that never ceases to make my hairs stand on end. The piece would continue to fascinate Fahey the composer as it evolved into numerous versions on the 1967 re-recording of this album, in numerous live recordings, and on 1971's America as "Mark 1:15"--each time expanding on the last but somehow leaving a trail of discrete incarnations, each with its own particular magic.

The dark corners of this album aren't without some extreme eccentricities, either, like the dissonant strumming on the flute duet, "The Downfall of the Adelphi Rolling Grist Mill" (Fahey's titles were often almost as great as the songs they labeled). Ultimately, though, Fahey's genius substantially rests on his ability to bizarrely marry the familiar harmony and structure of the blues with the dissonance and imagination of 20th century classical composers. For someone like myself who gets bored with the repetition inherent in a lot of blues music, hearing Fahey deconstruct his beloved genre and reassemble its innards into dazzling piecemeal sculptures breathes new life into what's usually a compositionally inert idiom. His preternatural melodic abilities provide melodic lines that sink into the brain slowly but insidiously--not sounding like much at first, but ultimately sounding as beautiful as any music possibly could--I really love the way his sweeping melodies traverse multiple string plucks, simultaneously savoring a note and impatiently re-sounding it before the sound has a chance to decay.

I've got a feeling that whichever Fahey album most people name as their favorite is one of the first (if not the first) that they hear. Though his early career covered expansive ideological and theoretical territory, it did so at a modest pace and Fahey would often repeat the same ideas either explicitly or intuitively. At the time he was only pressing hundreds of copies of each album, so how was he to know how things would sound when his discography was considered retrospectively? For example, he re-recorded and re-released most of the songs from this album (to be reviewed at a later date) in 1967, and the advancements he made in technique and composition are noticeable. What I'm trying to convey is that, beautiful as they are, some of his ideas lose that "first time" magic when they crop up elsewhere, and where you hear them first tends to remain the most memorable. For me, it was here with Death Chants, Breakdowns and Military Waltzes--I still think it's a great place to start with Fahey as it states many of the ideas he would continue to pursue--compositionally, technically, sonically (he'd continue to experiment with tape editing as the 60's wore on), and arrangement-wise (many more of his albums feature his own adaptations of Episcopal hymns as closers)--but it all comes in a relatively digestible form, mostly adhering to compartmentalized song structures and resonating with some sort of pop instinct in terms of flow and melody. I've got several John Fahey favorites, but this is probably the one I'd give up last--you can pry this album from my corpse's withered fingers.

Labels:

1963,

Blues,

Counterpoint,

Folk,

Good Guitar,

John Fahey,

Psychedelic,

Reviews,

Roots,

Solo Guitar

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment