The past year has been so busy with recording and evaluating my own music that I've had much less time to listen to other people's sounds, which means I've focused a lot more on the "new" music I'm finding instead of revisiting old favorites. When I do get around to albums I've heard many times, the experience is often quite illuminating. Especially after doing so much critical evaluation of music on this blog, I sometimes realize that my "5 star" albums, upon relistening, aren't necessarily free from the kinds of things I might label as "flaws" in other music, and that ultimately, designating something "as good as it gets" rests on a certain feeling of affection or nostalgia toward the music, or at least an assertion that the great things in the music are so good that any "flaws" come across more as endearing idiosyncrasies. In other words (and yet again), it's all subjective! The fun part about analyzing music in writing is the disjuncture between personal preference and the fact that yes, we actually can (and should) identify and judge specific characteristics in the music that justify how "good" we say it is, but also that "good" will always be individual, and reading music reviews and blogs is ultimately most useful as a way of pairing others' tastes with your own to discover music you might enjoy.

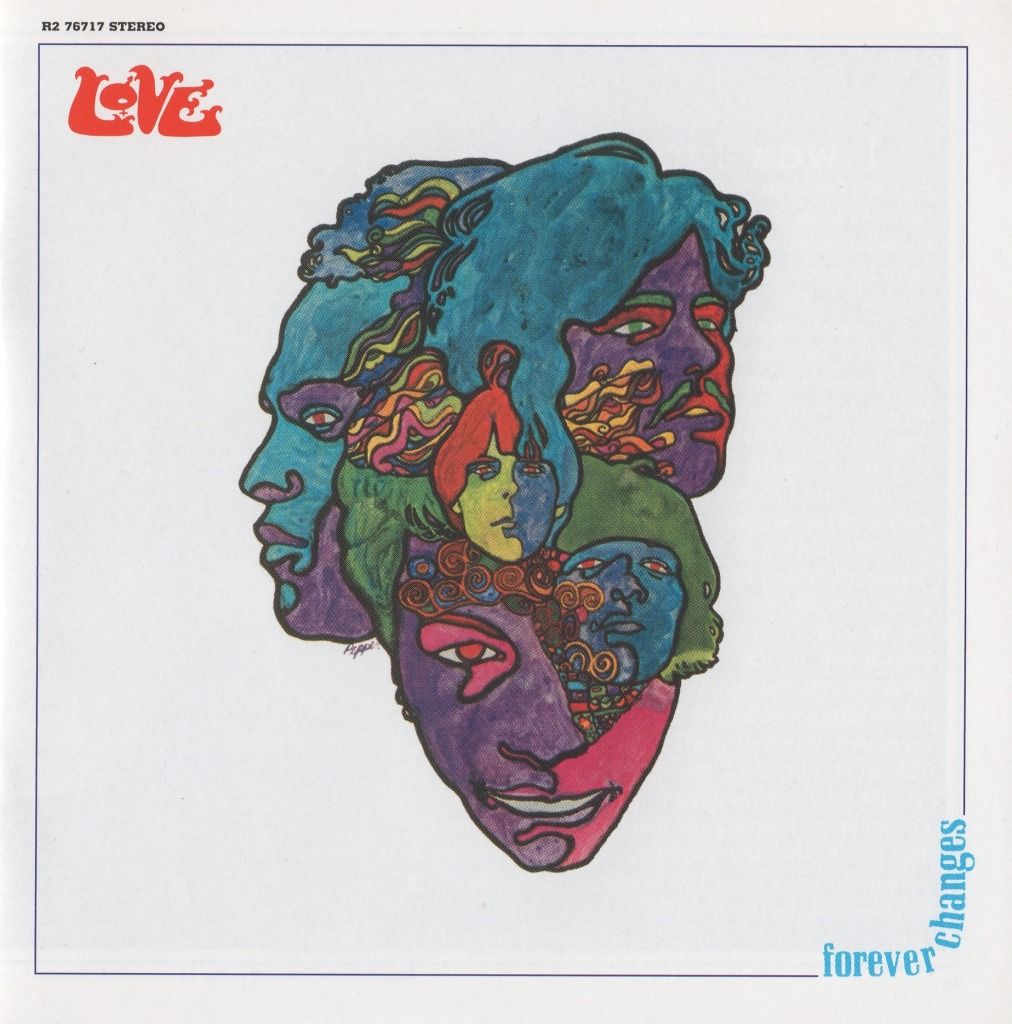

Forever Changes is one of those albums that winds up on innumerable critics' top lists, but has somehow kept a much lower mainstream profile in comparison with its contemporary "classics." You never hear any Love songs on the radio or in movies etc., and you'll be lucky if you hear anyone talking about them outside of musicians and critics. And yet, pick up Forever Changes and give it time to work its magic and you'll most likely understand why it quietly persists as a milestone in psychedelic folk-rock and as one of the best albums of the 1960's.

Like many great albums, Forever Changes is so great because it's often a bizarre combination of unquantifiable elements. There's the fact that it's a much mellower affair than Love's previous two albums--the more garage-like electric sound of Love and Arthur Lee's aggressive vocal style on Da Capo mostly replaced by acoustic guitar and orchestral textures--and yet it's still insidiously edgy. There's the album's unique twist on psychedelia, which often takes the form of hard-panned instrumental tracks (the nylon-stringed acoustic is so far to the right it's almost gone!) and brief additions of reverb as well as arrangement choices like having the background singers say a different word at the same time. There's Arthur Lee's obvious magnetism as a front man, which twists together the role of a sort of tormented seer with a dark fragility, surprising poetic capabilities, an ability to distill the countless clashing emotions of the 60's into songs that are simultaneously emotionally gripping and ultimately ethereal, as well as being a larger-than-life historical legend, somehow more than fulfilling Da Capo's thwarted potential here but quickly unraveling into mental and artistic instability (he was reportedly sure his death was imminent during the creation of this album) in the following years--still capable of creating good music but never coming close to reaching the same level of insight (especially lyrically) repeatedly on display here. And finally, in spite of Lee's dominant persona, there's the fact that the band was undeniably a collaboration, that Bryan MacLean's songwriting contributions and classical guitar contributions are as important to the album's success as any of the other elements, and that Lee's decision to disband the Forever Changes lineup soon after the album's release was a terrible blunder.

The distinctive characteristic that most people note about Forever Changes is the inclusion of orchestral arrangements, especially prevalent on the MacLean numbers--the balance is sweet and delicate on "Alone Again Or," "Andmoreagain" and "Old Man," songs whose optimism counterbalance some of Lee's desperate worldview with detours into romantic euphoria. Elsewhere, though, the strings and horns just as aptly provide a creepy, unsettling edge, as on the paranoid "The Red Telephone" and robotically closing "The Good Humor Man He Sees Everything Like This" (gotta love those Dylanesque 60's track titles), as well as brilliantly cathartic, as on the Latin-tinged "Maybe The People Would Be The Times Or Between Clark And Hilldale" (which boasts some of the album's most sly lyrical conceits, with expected rhymes interrupted by staccato horns only to appear to begin the next line...until the instrumental breaks, that is) and the transcendent album-closing "You Set the Scene." The cleverest part of the delicate arrangements is how well the rock moments stick out--"A House is Not a Motel" sounds like the heaviest rock you've ever heard, despite the fact that at least half of the song doesn't even have electric guitar, and the solo on "Live and Let Live" is insanely scorching because there's nothing "hard" to compete with it. Relistening I'm really surprised at how simple the arrangements actually are in comparison with the songs' complexity, usually consisting of just a standard two-guitar rock band with maybe a bit of piano and the aforementioned strings--the band's ability to make each part indispensable is a testament to the skill and care on display.

Lyrically, the album literally never lets up. While it's often difficult to discern what exactly Lee is singing about in each song, the impressionistic moments paint a collectively awe-inspiring picture of urgent searching, resultant disillusionment, distress, cynicism and ultimately grasping a fleeting sort of brilliant something that makes it all worth it...a something that might just be the absence of alternatives. Lee manages to toss out piercing one-liners right next to surreal scene-painting with the spontaneous force of a man possessed by something larger than his own conscious decision to create, and somehow manages to do so without completely slipping off the edge into incoherence. Despite the fact that the album is so very 1960's, his struggle and observations about the world's contradictions can't help but still ring true.

Perhaps this is the only truly great album Arthur Lee had in him, but its quality does seem to justify its singularity. Though it will likely always remain lauded but obscure, Forever Changes continues to humble me every time I revisit it--albums like this are something more than just old friends, comforting and diverting but always capable of teaching us something new.

Get it here

No comments:

Post a Comment