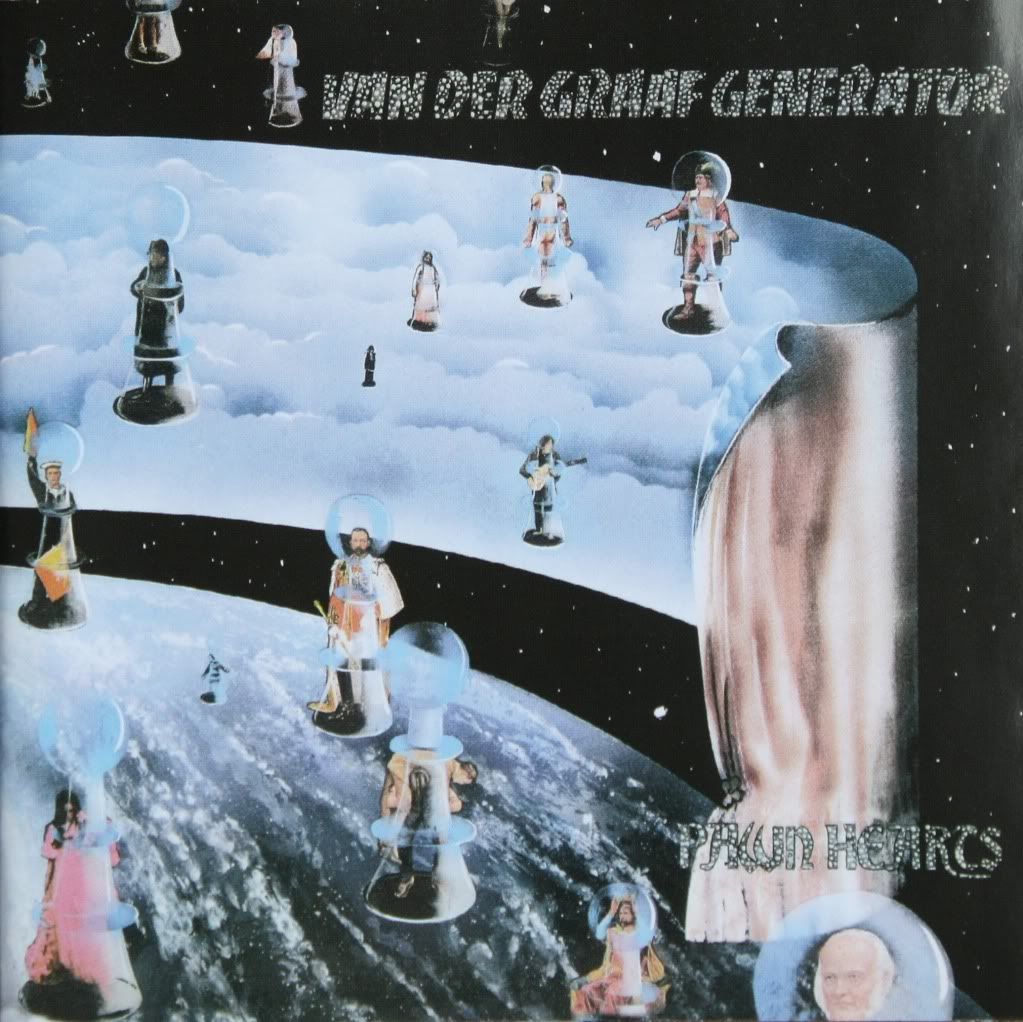

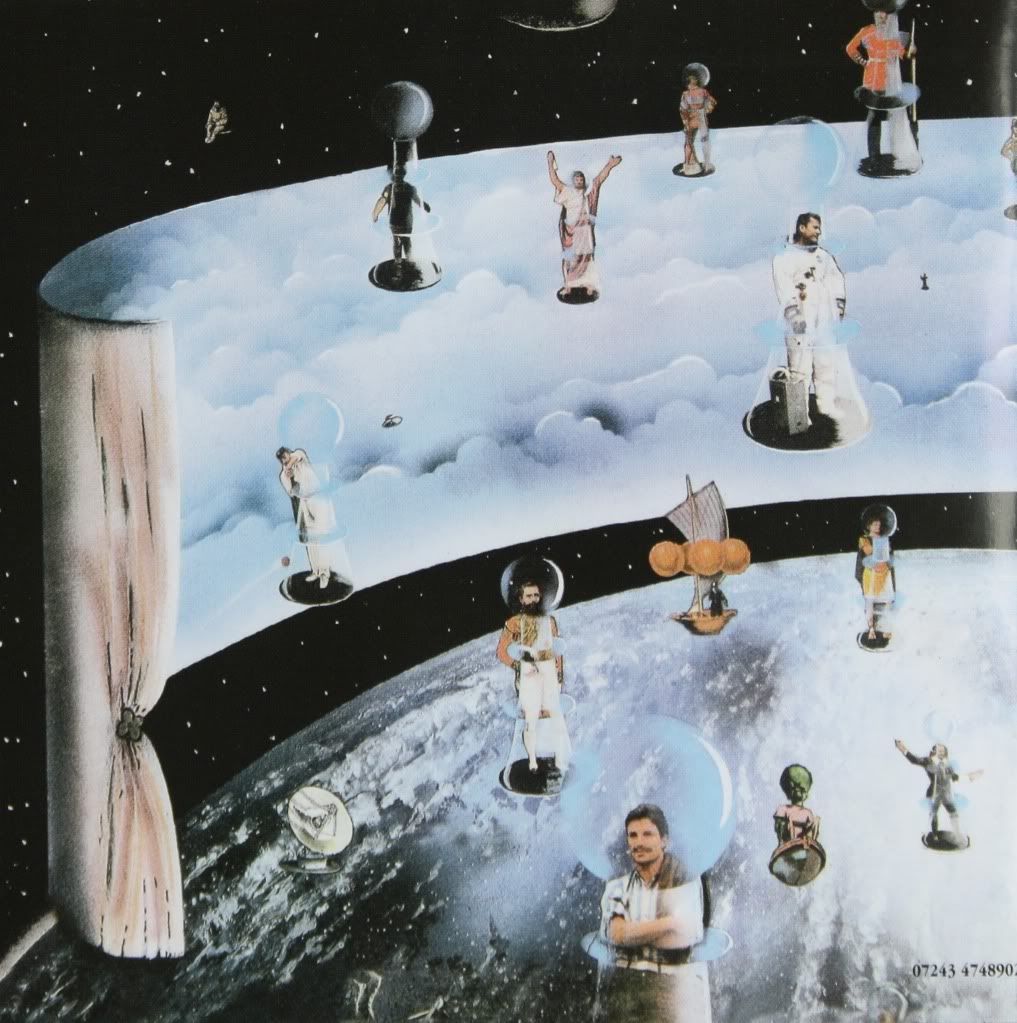

Though Robert Fripp and King Crimson are probably most widely-known as the dark lords of 70's progressive rock, I think Peter Hammill (who I've already introduced with Over) and Van der Graaf Generator do a better job of combining an ominous sound with focused lyrics that actually conceptually match that dark sound. I won't go into the group's needlessly convoluted history, but suffice to say that this was the last of the first four of their albums recorded before the band went on effective hiatus until their other masterpiece, 1975's Godbluff. Amongst the landscape of 70's prog bands, Van der Graaf Generator are known for being one of the best bands to largely avoid guitar in favor of a sound that combines unusually aggressive-sounding keyboards (Hugh Banton) and saxophone (David Jackson). The group additionally distinguished itself by being much more successful in Italy than in its native Britain, and by having a few of the worst-realized album covers in all of the progressive boom (and that's really saying something).

In my view, Pawn Hearts makes good on the promise of its predecessors, especially H to He Am the Only One, insofar as the band manages to flesh Hammill's lyrical and songwriting vision more cohesively and provide some of the most interesting, intense and engaging music they'd so far committed to tape. As I've kind of already mentioned, Peter Hammill is the deal-breaker for Van der Graaf Generator--you either like his balls-to-the-wall, theatrical, choirboy-cum-chainsaw vocals and find his perpetual interest in the blurry borders between psychology, metaphysics and science fiction compelling, or you simply don't. For me, his style is so original and varied that I'd probably like it even if I didn't find it aesthetically appealing, though I do occasionally feel he treads familiar lyrical thematic pathways a little too often (isolation being one). So, the Van der Graaf Generator sound is often expressed using Hammill's vocals as the prime melodic device, placing especial emphasis on his words and the drama of his delivery.

Like so many hallmark 70's prog albums, Pawn Hearts consists of only three tracks. The first two, "Lemmings" and "Man-Erg" could accurately be described as refined summations of where the band had already been. "Lemmings" is a sweeping expression of the album's concepts, describing mankind as lemmings rushing toward a clifftop. After a brief atmospheric introduction featuring Hammill's understated acoustic guitar strumming, the band launches into an odd-meter unison riff (one of their most distinctive devices) that powerfully joins Hammill's voice with the organ and saxophone. I'll readily admit that most everything Hammill writes is dark to the point of dourness and humorlessness, but I'll be damned if the hairs on the back of my neck don't stand up on end every single time I hear him sing "There is no escape except to go forward!" Though the subject matter is bleak, I think there's far too few lyricists willing to face up and address the particulars of humankind's ultimate destination and looming self-destruction. Not that they need necessarily be addressed so grandiosely or even darkly at all, but for me it's a refreshing change of pace from the blithe escapism offered by most pop music. Across the song's mottled landscape (there are all kinds of great singular moments built into the composition) Hammill's desperation grows to the point that he pleads, "What choice is there left to die/in search of something we're not quite sure of?" The song's rousing middle section combines an interlocking riff based on Jackson's dual saxophone (he'd play two at once) and Banton's juicily-overdriven organ. By the time the song winds back around to its recapitulation and climax, it's apparent that Hammill's outlook isn't quite as pessimistic as it originally appeared--in the face of an indifferent universe, he decides, "What choice is there left but to live/In the hope of saving our children's children's little ones?" The humanistic message rings in the air over one of my favorite parts of the song in which two of the melodic themes overlap and repeat, warping each time into an uncertain haze, musically complicating Hammill's conclusion.

"Man-Erg," perhaps best described as a power ballad, weaves a well-trod style for the band with the Pawn Hearts concept (which I interpret to generally encompass the unsure and unstoppable motion of the human race and each human's seemingly insignificant role in it--both externally and metaphysically). As the lyrics quote from the band's earlier works (both "Killer" and "Refugees"), Hammill passionately treads the floorboards over his dual nature as a killer and an angel, eventually realizing that he encompasses all aspects of human nature. The song's deliberate but anthemic pacing as well as another aggressive and dissonant middle section with some frenetic vocals set the track apart from some very similar earlier ballads in the group's history, and some jazz harmony in the second half adds a welcome dimension to the relatively straightforward ballad style.

"A Plague of Lighthouse Keepers," the album's 23 minute-long second half, is predictably less focused. The epic track trades straightforwardness for some of the album's most spacious atmosphere, though, and it's also got some of the most musically progressive composition of the band's entire output. I've heard a number of listeners write the song off as directionless, which I think is easy to do when a song is over 20 minutes long--personally, I think it takes quite a few plays and some close attention before songs like this really open up and I try to withhold judgment until I've at least listened enough to recall from memory the song's general structure and some of the melodic elements. If I'd written this review six months ago (even after having heard it many times over the course of two years), I'd be far less kind to this song, but I've come to appreciate its many nooks and crannies, wealth of melodic ideas and repeated brazenness much more in the interim. I still don't feel like I've got a strong grip on the lyrical subject matter (the beauty of forming a long term relationship with good albums), but I think the song's strengths certainly outweigh its weaknesses, with some breathtaking unison arpeggios, some of the most searing dissonance on the album, and some genuine scariness. I would say, though, that the 70's progressive period did produce a few more cohesive epics; "Lighthouse Keepers" at times plays like several nearly-a-song sections interspersed with musically interesting but somewhat unrelated vignettes. For an epic of this length, I'd hope for a little more unified purpose, but the parts are of high enough quality that it's still pretty engaging.

I've maintained for a while now that, though it may not accurately be described as the way "forward," atonality in both melody and harmony seems to be the most shamefully underutilized 20th century music advancement of all when it comes to pop music. Instead of passing the last 100 years retraining our ears to appreciate the innumerable combinations and "millions of colors" possible through the varied application of atonality, we've clung to practically the same conservative, inflexibly traditionalist, oh-so-Western, "16 colors" conception of harmony we've been fearfully clutching more or less since Beethoven. It's with great pleasure that I welcome this group's experimentation with atonality in "Lighthouse Keepers'" more violent sections as well as the depth it adds to some of the more ethereal passages. Though 70's progressive rock eventually became hated by some for its less attractive aspects and exponents, to the point that the word "progressive" almost exclusively conjures sounds of Hammond organs, Moog synthesizers, romantic composition and 20 minute songs, I long for a future in which the word "progressive" returns to its literal meaning and can be used to describe music whose intent is to continue music's progress and (ideally) perpetual journey to become something it wasn't already before. Sadly, we've instead got "Art Rock," "Experimental," "Post-Rock," "Post-Punk" and "Noise" all using increasingly vague synonyms to distance themselves from the period flavor of 70's progressive music when in reality they're often attempting to achieve similar goals. That said, I think Van der Graaf Generator (though obviously of the 70's in sound) puts a distinctive spin on the period's common tropes and provides enough interesting experimentation that they're still worth checking out and deserve their cult status as one of the best of the original waves of progressive bands. While I don't think any of their albums are flawless, I do think the uncommon number of risks they take more than adequately justifies the flaws.

In celebration of the horrible album art, here's the back cover.

No comments:

Post a Comment