Thursday, September 15, 2011

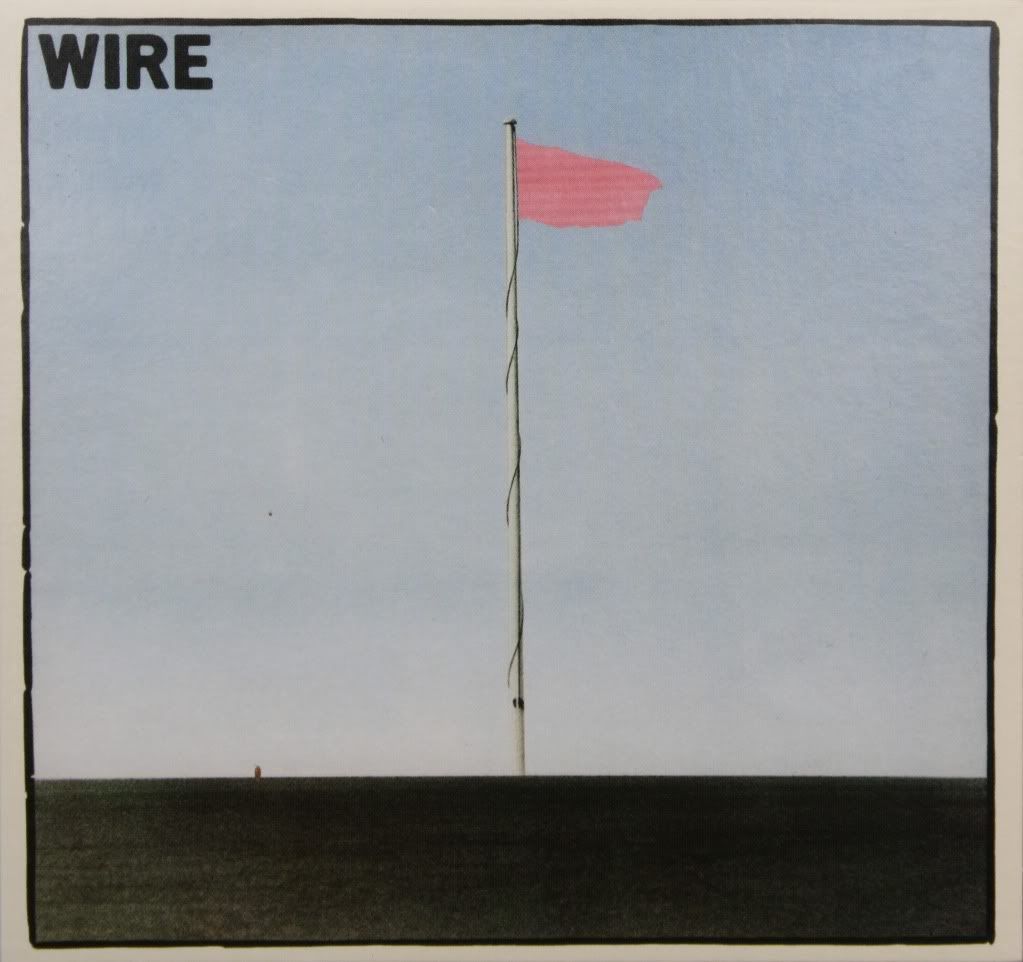

Wire - Pink Flag

It's pretty heartening to see that, even in the heyday of British punk rock's emphasis on simplicity and aggressive emotions, there were still a few bands willing to marry those ideals with intelligence, experimentalism and a high level of attention to creativity. While I freely admit it's not my most-explored area of interest or expertise, I can easily say that of all of the "post-punk" outfits I've heard, Wire--at least on this album--bears the strongest aural relationship to actual punk. The genius of Wire's debut is how the band manages to fashion punk's back-to-basics aesthetic and vitriol into a new incarnation without turning to elements of the psychedelic, experimental and progressive music against which punk was supposedly a reaction, which is more than can be said for most of the other post-punk bands I've heard.

Probably the most impressive twist Wire makes on the punk formula is one that can actually be productively applied to all types of music--they make an effort to turn each song into a terse statement where the ideas are clearly stated but not smothered to death through repetition. The result is a 21-song, 35 1/2 minute-long album with nary a wasted second and a shining wealth of ideas. Lately, this pursuit of succinctness is one that has interested me more and more both as a musician and as a listener. The beauty of Wire's solution is that the ideas are oftentimes stated only once--though some songs have repeating verse and chorus structure, there's also some more through-composed pieces like "Field Day for the Sundays," which subsists on about 2 riffs (one of which becomes even shorter when it returns at the end of the song) and is over in 28 seconds!

It seems the concept's successful application hinges on a delicate balance between the quality of the ideas and how often they recur. While Wire often finds artistic success in paring down their songs to sub-1-minute lengths, I don't think short song lengths are necessarily the only way to successfully implement brevity. It seems to me that the real enemy here is excessive repetition which, in my mind, is the not-so-silent killer of interesting ideas and the bane of a huge swath of popular music both past and present: an artist takes what once was an interesting idea and hammers it into the ground with repetition (either in the same song or across multiple songs) providing little or no variation or expansion on the original idea. With ideas stated so sparingly, the songs never overstay their welcome; while some might argue that this approach is deficient in terms of development, I don't see an issue when so-called "development" usually just consists of to-the-note repetition. As a kindred creative spirit, I think the grace of this type of brevity is that the development or repetition of an idea is implied and left up to the listener's imagination and previous experience. Our ears are accustomed enough to melody and structure that, if we're paying attention, it's easy to extrapolate a brief idea and fully complete the relatively unimportant repetitive material that isn't there with the condensed pith that actually is. Rather than heavy-handedly forcing the melodies and ideas into the listener's memory, this method alluringly waits for the listener to meet the ideas halfway, and for me this engagement is a large part of the fun; further listens reveal more and more as the ideas expand in your head. If you want to hear more of the same riff--listen to the song again. Meanwhile, the artist is able to focus on surprising the listener's ear with the next idea rather than providing it with ear-predictable chaff, and can potentially pack more ideas into one album than many bands manage in an entire discography.

Now, it's not that any repetition is bad or even that conciseness is the only way to pack music with ideas (compositional guidelines for development in classical music and improvisational comping in jazz are a couple of examples of traditions in long-form music that manage to keep the interesting ideas flowing). The point is that we've gotten somewhere interesting--we're now focusing on ideas as the building blocks of good music; the interesting and infinitely-discussable issue of whether we fully agree on the method becomes more of a matter of preference, subordinate to the more important common goal--the avoidance of a zombie-like, by-the-numbers approach to music.

Of course, short track lengths alone don't guarantee great ideas--luckily, Wire hold up the other end of the bargain. Despite the fact that the songs are pretty much exclusively guitar-bass-drums, the band manages to squeeze what seems like a limitless number of great riffs, vocal arrangements and hooks out of such classic instrumentation. The songs range from the juicy distortion of anthemic punk sing-alongs like "Ex Lion Tamer," "It's So Obvious" and "Mr. Suit" to some glorious, occasionally light-hearted hard pop with the likes of "Three Girl Rhumba," and especially "Fragile" and the ridiculously catchy "Mannequin." I also really like how well they manage to meld the punk ethos with more experimental (and occasionally slower) material, like the album's dire opener, "Reuters," the detuned rage of the title track, and the simultaneously bluesy and weird "Strange"--the album's longest track at 3:59. Special mention should be made of the sometimes impenetrable but always evocative poetry (thanks, I think, to vocalist Colin Newman) that makes up the lyrics. While Newman's suitably untrained and raw delivery often makes understanding the words difficult, searching some lyrics on the internet gives the already engaging music even more depth and helps the songs' linear structures make even more sense.

Like a lot of classic albums, Wire's debut will please more than just punk fans with its pop sensibility, experimental edge and timeless rock and roll spirit. While it's sort of easy to understand that the band's creative approach guaranteed the album's initial commercial failure, today it's seen by most as a classic and probably the purest example I can think of to illustrate the type of idea-to-minute ratio that more artists should aspire to.

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

2 comments:

wow! unexpected review on this blog. I like reading your opinions about punk and post punk. music is rarely exclusively reactionary; and i often consider punk in the same tradition as psychedelic and synthesizer experimentation of which many critics see punk as revisionist and contradictory form. Mark E Smith (of post punk band the fall) would describe his music as Head music. That's why your reviews are so great, because you deal almost exclusively with what I would consider Head music. keep it up Elliot! Got any shows coming up?

Hey Peter,

Thanks for reading, as always--I'll see if I can keep a couple more surprises coming. Clearly, over-intellectualizing the subject is my Achilles heel!

Funny you should mention The Fall--after my great enjoyment of Wire's first 3 I decided to check them out. Much more like what I'd expect from "post-punk," but pretty good too. Do you have a favorite album or two of theirs (I picked up This Nation's Saving Grace)?

I may have a show coming up during Reverb, I'll let you know. Mostly working on demoing some new songs right now. Just picked up your band's new EP...

Post a Comment