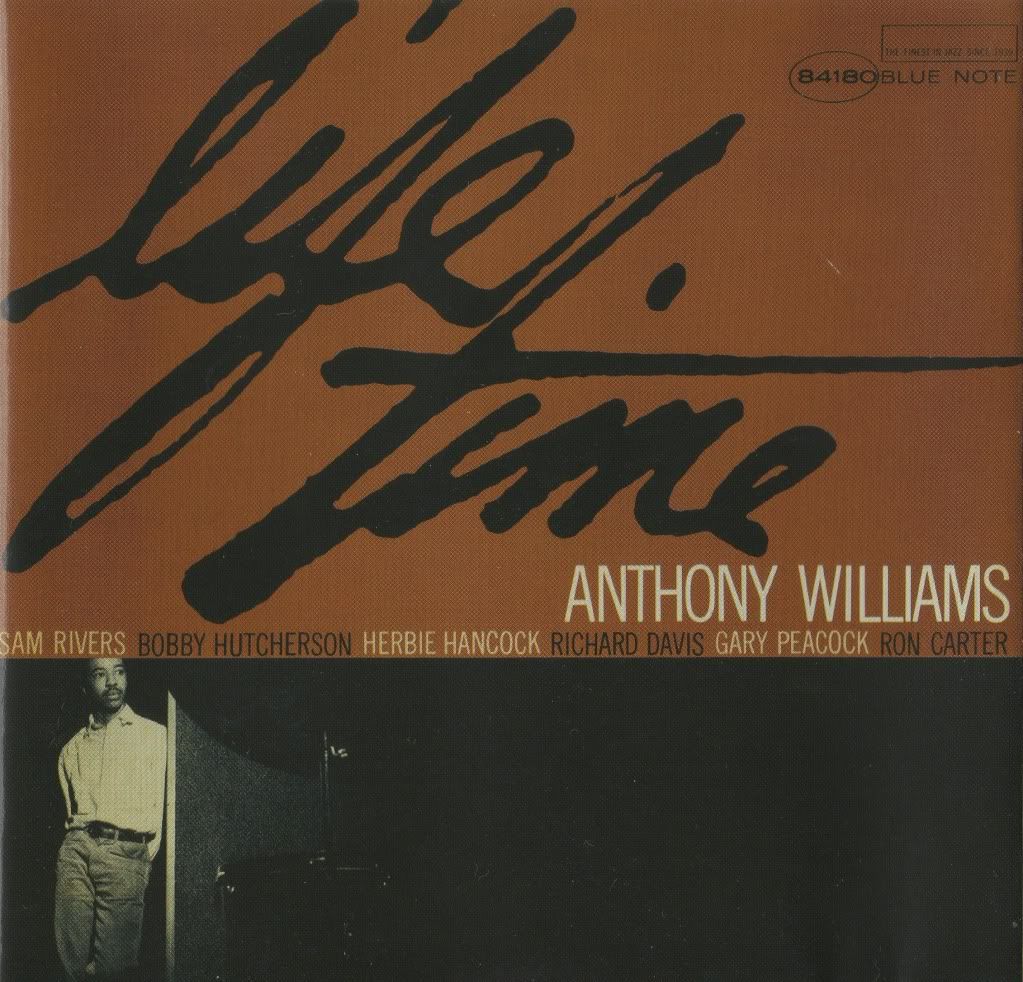

By 1965 and this--drummer Tony Williams' first set as a leader--the then-17-year-old had already been working with a slew of talented and innovative jazz artists, including Herbie Hancock, Eric Dolphy, Andrew Hill, Sam Rivers, Jackie McLean and Grachan Moncur III (not to mention his recent incorporation into Miles Davis' Second Great Quintet). Listening to Life Time, it's clear that Williams was listening closely to what the latter two were doing, especially on the sessions for McLean's One Step Beyond and Moncur III's Evolution. For me, this album represents one of several high points from the period when it comes to a distinctive brand of avant-garde jazz that seems to favor space over wild soloing.

You know from the eerie, quietly intense opening melody of "Two Pieces of One: Red" that this isn't going to be a typical bop album, but as Sam Rivers' tenor fades out and dual bowed basses from Richard Davis and Gary Peacock gently arpeggiate it's apparent that this subtle opening isn't going for the explosion your ears might expect. One of the bassists takes the first solo, and from then on you can rest assured that we're not returning to the usual structures or sounds for the rest of the album. "Two Pieces of One: Red" and the rest of Life Time are typified by a restrained, spacious atmosphere wherein solos take place with very little backing instrumentation (aided considerably by the fact that there's no piano on three of five tracks) and rarely take off into the rapid-fire solo excursions popular even with some of the players on this disc--Sam Rivers is surprisingly subdued here, but he manages to ride the transition with little difficulty, relying more on dynamics and the presence/non-presence duality that's much more of an option when you're playing in a musical landscape as open as this one. Indeed, the overall sound of this album owes as much to the theoretical advancements of John Cage as it does to free jazz pioneers, setting up blocks of silence as both an effective compositional tool (making it easier to tell when the sometimes skeletal compositions are moving to another section) and as an invisible member of the combo, giving the players another (absence of) sound to play off and somehow adding depth and intensity to the sounds that are actually present. Williams' drums in particular seem to particularly smolder in the open, reverb-heavy environment, with his brushwork lifelike in its texture and his cymbal work especially benefiting from miles of reverb and a lack of competition with other instruments (and himself, for that matter--this music wouldn't be so great if the players didn't match the mood by leaving a little space in their own playing).

"Two Pieces of One: Green" is the album's longest track, with Rivers contributing some more of his characteristic fire and blasting some really juicy overtones, while Williams explores the toms and un-snared snare. While the subtle melody of some of the album's other tracks gradually reveals itself, this track is one of the freest of the bunch, demonstrating amply that free jazz doesn't have to always consist of several instruments blaring at the same time. "Tomorrow Afternoon" comes closest to hard bop in melody and swing, but gradually breaks up into greater and greater caverns of space, like the floor is dropping away from the comfortable atmosphere that was so briefly established. "Memory" drops Rivers and brings vibraphonist Bobby Hutcherson and Herbie Hancock in for a bassless free improvisation that sees Hutcherson and Williams riffing off one another quite effectively, with the vibes providing just enough of a tonal anchor; with Williams' wood block and other hand percussion providing yet another noticeable textural contribution. The arrangement is so sparse that when Hancock finally asserts himself around 5:30 with a brief chord, it sounds like the loudest, most melodic thing you've ever heard. The album ends with "Barb's Song to the Wizard," a piano and bass duet with no drums--the tense melody nods to Williams' aforementioned work with Moncur III and McLean. Unlike those great albums, though, Williams always seems to take things one step further, providing no real traditional bop tunes to appease nervous listeners and committing fully to the album's mission statement.

The fact that this album works so well with such a piecemeal, rotating assortment of players exclusively playing the compositions of a 17-year-old drummer is a testament both to Williams' skill and unheard-of musical maturity at the time, but also to whatever it was in the air at the time that made all of these players so assured in their judgment, synchronicity and adventurousness. Life Time is a grower in the best sense of the word--sounding like nothing much on first listen but gradually unfolding into a paradoxically dense work, considering its relative quietness--and every time I listen to it I find myself asking "Why isn't there more free jazz like this?!" Luckily a little research into the discographies of the artists involved here yield further pairings in the same time period and several great albums in the same vein. While Williams would go on in the next few years to collaborate with some of avant-garde jazz's most acclaimed albums (as well as Miles Davis' less challenging but equally iconic work [I bet he hated this album]) before heading into fusion territory, he did reconvene with some of these players for the nearly-as-excellent Spring, but no album I've found has done such a good job of fusing an AMM-like free improv space aesthetic with "traditional" free jazz harmony and melody--recommendations welcome!

Get it here

No comments:

Post a Comment